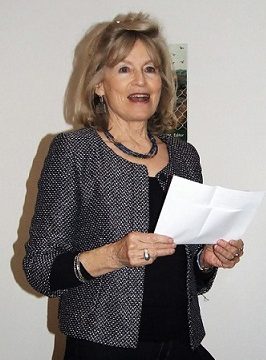

She spent most of her lifetime fighting in the frontline, speaking up for the human rights of those who are not powerful enough to raise their voice. Not seeing herself as an activist, she just tries to hold onto the truth she sees with her own eyes, and be true to her beliefs.

Yi Zou

“Often I have young people come up and say: ‘you always write to our MPs, tell everybody about these issues but nothing changes, so aren’t you a failure?’ … But I keep doing it, because what is the alternative? You will just have to keep going on.”

These are some words from writer Victoria who has dedicated her life to those who suffer from the persecution of The War on Terror and the prisoners in Guantanamo Bay.

In 2003, she joined a group who were planning to put on a theatre production, and was responsible for collecting verbatim statements from the families of those who have been arrested and incarcerated in Guantanamo.

After hearing so many shocking stories about them, speaking up for these people turned from a simple job into a lifelong mission. Born in India, she left for Britain at an early age, but she always wanted to go back and wondered about her birthplace.

With years of working experience in Asia, the Middle East and West Africa, this former Guardian journalist showed The Prisma her unconditional dedication. Right after the interview, she was about to have her Arabic class, a language which interests her greatly, although she finds it difficult.

Are you British, why were you born in India?

Are you British, why were you born in India?

Yes, I am British. My father was part of the so-called British Empire and he was like a leftover from that period. I came back to the UK when I was about three or four.

I assume not many British people were born in India?

Of my generation there are many, (…) but even though the empire was more or less finished, there were still people who worked in banking, or the British governor who remained there until the partition in 1947 .

What brought you to work on Guantanamo?

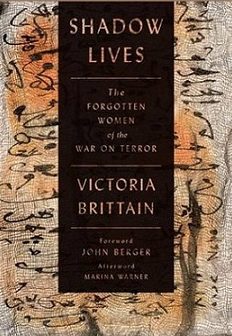

When it first happened, people didn’t know what it meant or who was in there; at the beginning they did not give the names of the people who were there. There were about a dozen families where the man was either British born or a British resident and they were picked up from all sorts of different places: Afghanistan, Pakistan, West Africa… The families were saying “What has happened”: they suddenly stopped getting their letter. If you get Shadow Lives and read the beginning, you will understand that the random way in which people got picked up was just extraordinary. I was part of the team that did a play using the actual words of the families here talking about their sons or their husbands, brothers.

At that point, were you working for the Guardian?

I think I had just left or I was about to leave. (…) It was 2003.

What was the team doing?

What was the team doing?

There was the man who owned the theatre, there was another writer, there were actors who were playing different men, and people who did the design and the costumes.

My job was a small thing, to talk to people and record the words of the families which could be used in the play. I was completely shocked by what I heard. Because the way people were arrested was very random. It was not that somehow they had got involved with the Taliban. It was random, so some of the families – I guess they liked me and they asked me to help to do campaigning with them, organising public meetings and so on.

Was it based in London?

London, and somewhere in Birmingham, somewhere in Manchester; it was all based in Britain.

These people got arrested outside, but their families were in the UK?

These people got arrested outside, but their families were in the UK?

Sometimes the families had been with them in Afghanistan, like aid workers for example. When the Americans began to attack Afghanistan, the men sent their women back to Pakistan and eventually back to London; and the men stayed to look after the house and they got arrested. The North Americans pay Pakistan and Afghanistan to give them foreigners. They offered 5000 dollars for Arabs because they thought the Arabs were all Al-Qaeda or something like that.

It is like they are buying a quota?

Exactly. If you have not followed this, you will be really incredulous . So shocking. I became very interested in all of this and very friendly with the lawyers, (…) so I became interested in a sort of personal way with women who became my friends; but also because the whole War on Terror was a period in history people look back on with horror. How could we have been part of something that was so illegal?

When you become friends with these women, do you think you can still maintain your objectivity as a journalist?

When you become friends with these women, do you think you can still maintain your objectivity as a journalist?

I have done a lot of teaching in journalism schools and a lot of young journalists come to ask about that.

I always say that when your teachers tell you that you have to be objective and that you have to make the balance between one side and the other, it’s not really true. (…)

You have President Bush and Defence secretary Rumsfeld who would say to the media all the time: “these people are the worst of the worst, these people would kill with their bare hands” – which is completely untrue. People believed it because it was everywhere in the media. (…) I would not use the word ‘subjective’ I think it is better to say ‘truthful’. Because you come with your life experience, the things you know, your attitude from the life you have lived and you bring that with you. (…) But what you can do as a journalist is to commit yourself to being truthful. (…) I could not say that what the Americans say about these people is worth the same as what actually happened to them.

Do you see yourself as a Human Rights activist for these people in Guantanamo?

Do you see yourself as a Human Rights activist for these people in Guantanamo?

I do not particularly like the word ‘activist’, because I think it is everybody’s duty to be active in life. You have to be involved in the world. If you know about the injustice in Guantanamo, you speak about it when you get the chance, you write about it, you talk about it, and you work to support those who are trying to do something about it. I am a writer and that is what I do.

In general, do you think the mass media is doing a good job in informing the public about these injustices?

No. Yet what is great nowadays is that because of the internet, many web-based newspapers and magazines are doing what you are doing; different points of view get written in more detail, and from more different perspectives than anything that would be in the mass media. (…)

I think the fact that all the big newspapers are losing money and losing readers is partly because people do not trust them so much, or are not interested in them so much because there are so many different ways of reading about the world.

I think the fact that all the big newspapers are losing money and losing readers is partly because people do not trust them so much, or are not interested in them so much because there are so many different ways of reading about the world.

What is your opinion about countries having no borders?

It will never happen. What I feel strongly about the present situation of refugees in Europe is that our country has been absolutely shockingly ungenerous in accepting refugees. Earlier this year, I was in Lebanon, the poor country was overwhelmed by refugees. If you see what the Lebanese are doing, they are very nice, they build schools, they give land and houses so that refugees can have a life, (…) I went to one school which (…) was just a voluntary contribution made by ordinary people, and I can give you dozens of examples of this. Whereas here in Europe, their attitude has been like “it is not our problem”. (…) We have created these refugees and the instability, but we do not want to do anything about it.

What do you think of Theresa May’s attitude towards the refugees?

I am not fond of this government, they have been much too slow, much too ungenerous, and have not developed a kind of leadership for people in this country to welcome refugees.

That’s why this country is very bad at the moment with all this xenophobia. Outside London, there is much more xenophobia and it has been encouraged. The whole question of the Brexit vote – all full of racism – encourages people to think that it’s okay.

That’s why this country is very bad at the moment with all this xenophobia. Outside London, there is much more xenophobia and it has been encouraged. The whole question of the Brexit vote – all full of racism – encourages people to think that it’s okay.

Do you think there are enough journalists to provide sufficiently different points of view for the situation in Guantanamo?

There are never enough. Guantanamo would have been closed long ago if everyone had kept on writing and speaking about it. A lot of people have worked on this issue, we have had some successes, (…) but overall I am very angry that we are not being more successful.

Currently, how many people are still in Guantanamo?

Sixty. About half of them are cleared but not yet released. There are other people that they call ‘forever prisoners’, about seven or eight.

They say they are not being charged with anything but “we don’t think they are safe to release”.

They say they are not being charged with anything but “we don’t think they are safe to release”.

Based on what?

Exactly. Based on secrets that we do not know about.

Will you still keep working on Guantanamo?

I’m afraid I’m completely involved in it. I have no choice.

(Photos form Pixabay)

.jpg)