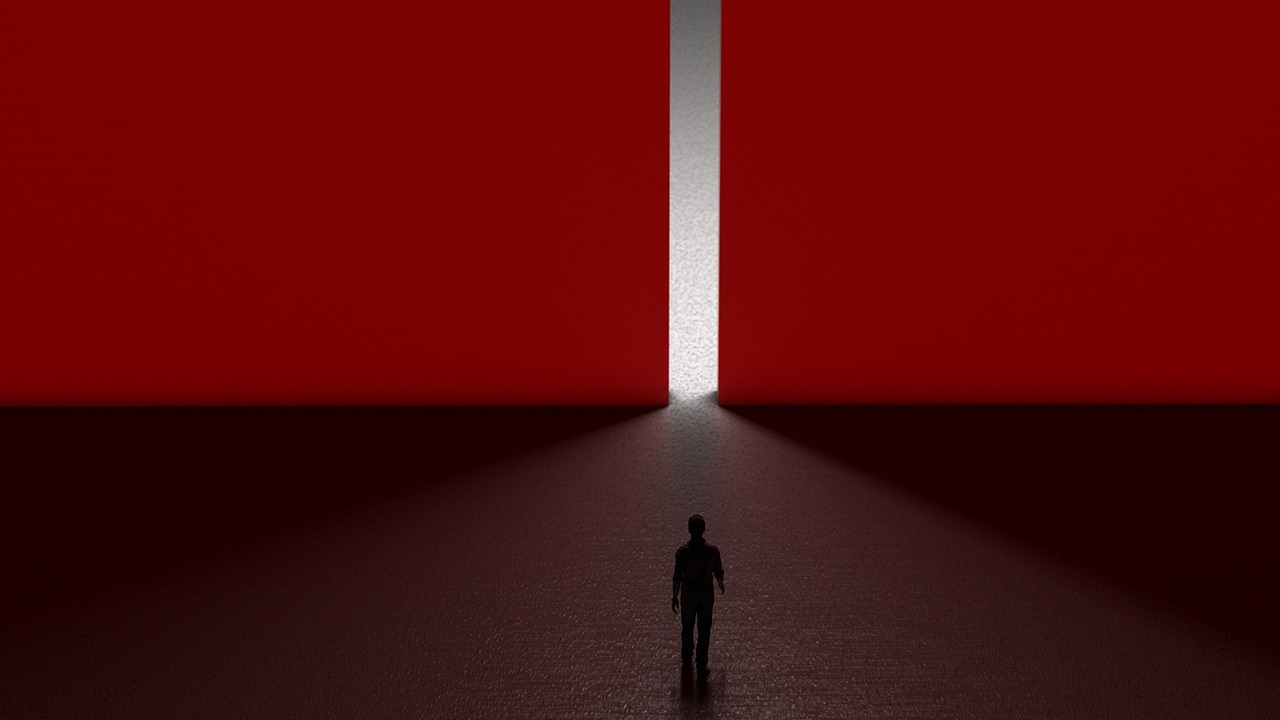

Uncertainty and fear of being deported at any time, this is what awaits immigrants who do not have the necessary residence credentials to live in the UK. And the first stop is their worst nightmare: the detention centres.

Virginia Moreno Molina

Virginia Moreno Molina

At work, waiting for a bus, having a coffee or any other daily activity, officials can approach an immigrant any time and to ask to see their documents.

And immigration officials are not the only ones doing this. The police are too. Once detained these immigrants’ naivety and desperation makes the whole process of obtaining residency all the more difficult. It was 7 am and Anastasia*, a Colombian national, was waiting for her bus to work. She was in a hurry and busy looking at her watch, which is why she did not notice the two police officers approaching her from behind.

Ramiro* from Guatemala was sat on the sofa watching television at home with his flatmate. All of a sudden they were startled by a few loud knocks on the door. Neither of them was expecting company but when they opened the door they were greeted by two people in uniform.

Aida who is of African heritage was cleaning in an office when she heard the sound of cries and struggling on the ground floor. She had no time to react, when she looked around she realised she was surrounded by immigration officials.

All were asked the same question: “Documents?” And their lives were turned upside down. Like them many hundreds and even thousands of immigrants have been wrenched from their daily lives be it while working, waiting for a bus, having a coffee or any other daily activity.

All were asked the same question: “Documents?” And their lives were turned upside down. Like them many hundreds and even thousands of immigrants have been wrenched from their daily lives be it while working, waiting for a bus, having a coffee or any other daily activity.

Initial questioning

The police take immigrants to the station to check their details. Home Office agents (immigration officials) conducting raids detain them and subject them to a series of questions (name, date of birth, address) and then check the details on a database to see if they are here illegally or not.

If the police find that they do not have the correct documents or if they simply do not speak English, the police detain them and bring them to the Home Office to interview them regarding their situation in the country.

At this time a decision is made as to whether to send them to a detention centre or release them. In the case that they have a European partner and can demonstrate this they can be released.

However a different fate awaits those who cannot. They are photographed and their fingerprints are taken to register them on the system. The next stop is the detention centre.

Forms and lack of information

Forms and lack of information

It is here in the detention centres – these are located in and outside London, in the suburbs and in the north of England, where detainees like Anastasia, Ramiro and Malu are held. These are just three names out of the raft of detainees waiting for their cases to be decided.

They can be held here for weeks, months and even years. In the case of Latin American detainees their cases tend be decided quite quickly, though this is not always the case.

All detainees have two options: to be released under temporary admission or bond. The forms for this are available and detainees can apply using the forms themselves or with the help of a lawyer.

In the case of temporary admission the applicant must give an address where they can be reached once released. But if they decide to take the bond option the amount is extremely large (from £ 1,500) and a court judge has the final word on whether release should be granted. Despite this detainees are sometimes ignorant of what they are up against and the various options they have at their disposal.

Where there is a law there is a loophole

In the Charter for Human Rights articles 3 and 8 relating to family indicate that “a detainee who has an English partner or one from the European Union; who has children with their partner; or is between 10 and 14 years of age living in the UK can hire a lawyer or ask for a duty solicitor to be provided and make an application this way”.

But the Home Office has its own firms of lawyers who represent them unfailingly against all immigrants regardless of the individual case or situation.

But the Home Office has its own firms of lawyers who represent them unfailingly against all immigrants regardless of the individual case or situation.

An example of this in practice can be seen with detainees who have a partner from the EU.

Filing an application for release under bond their documents often take a long time to come through so the Home Office exercises its right, a few days before the judge’s decision can be made, to send the detainee notification of their imminent deportation back to their country of origin.

Home Office lawyers then argue once at court that detainees have just few days to leave the country and the process for deportation is already under-way. This is often the problem immigrants’ lawyers are faced with. And while there are good lawyers who have a full grasp of the job they are entrusted with, there are also incompetent ones who do not know how to deal with these kinds of cases and sometimes the story ends with the immigrant being deported.

Propaganda purporting to the easy life of detainees

Detention centres have gyms, book shops, open spaces with gardens and even churches. This is how firms like Serco publicly portray immigrants’ lives in these places. But the reality appears a far cry from this: there are some who fight for their rights and other more vulnerable victims who have lost hope and await notification of their deportation.

And so suicide attempts, self harm, hunger strikes and protests etc. are daily realities. Realities these firms prefer not to advertise.

And so suicide attempts, self harm, hunger strikes and protests etc. are daily realities. Realities these firms prefer not to advertise.

This is why some of the centres do not have internet access and detainees are not allowed telephones with inbuilt cameras, so any attempt at exposing this reality with video evidence of the inside of the centres is impossible.

Outside

If they are very lucky, detainees like Anastasia, Ramiro, Malu and thousands of others will be released.

But even after having endured days, weeks, months or years in these centres their rights are constantly questioned on the outside.

Since the harsh policies on immigration came into force, immigrants lives have taken a turn for the worse.

Whether here legally or not they all have to jump through several hoops to get the most basic needs: accommodation, work and bank accounts, among others.

And so each time a Colombian, African, Guatemalan or any other non- EU resident applies for a job, open a bank account or move home they will be subject to the same question time and again: “Do you have documents that state you have the right to reside in the UK legally?”

And so each time a Colombian, African, Guatemalan or any other non- EU resident applies for a job, open a bank account or move home they will be subject to the same question time and again: “Do you have documents that state you have the right to reside in the UK legally?”

And indeed Governments have encouraged British citizens to blow the whistle on illegal immigrants.

*(For security reasons the names have been changed.)

(Translated by Nigel Conibear – Email: nigelconibear@gmail.com) – Photos: Pixabay

.jpg)

Thank you for exposing the issue. I am going through similar ordeal in the United States. Thus I can testify from the experience how true your words are.