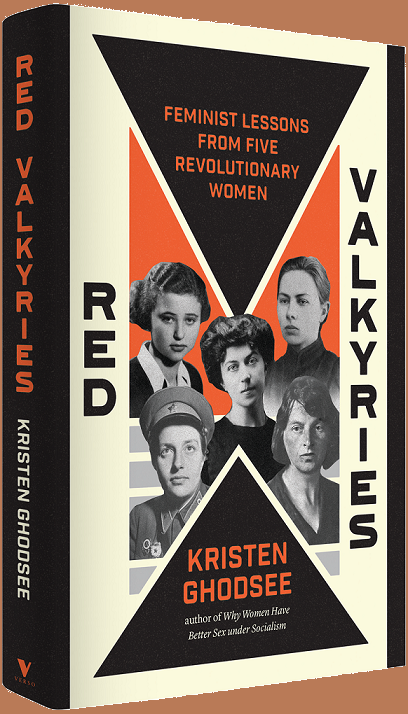

“Red Valkyries” is a very engaging and informative account of five remarkable women from the time when Eastern Europe was part of the Soviet Union.

Sean Sheehan

Readers may know about some of them, if only by name, but probably not all five, making this book a valuable contribution to knowledge of socialist women who challenged the way things were.

In debates at the Third Communist International Karl Radek called one of them a valkyry –females in Norse mythology who guided souls to Valhalla– and Kristen Ghodsee’s book suitably concludes with an account of how the five women’s political projects help guide the way in current struggles.

The first and final of the five women are the least well known.

As a killer of men, 309 in total, Lyudmila Pavlichenko could be labelled a mass murderer but she was a Ukrainian sniper in World War II fighting an invading Nazi army fuelled by race hatred and with the intent of enslaving her people.

She said she was saving lives and, when questioned how she felt about shooting in cold blood, asked her own question: ‘How can a human being feel when killing a poisonous snake?’ It is not obvious how to argue that she was wrong in doing what she did.

She said she was saving lives and, when questioned how she felt about shooting in cold blood, asked her own question: ‘How can a human being feel when killing a poisonous snake?’ It is not obvious how to argue that she was wrong in doing what she did.

Elena Lagadinova was born in Bulgaria in 1930 and was running food and messages to guerrilla fighters while Pavlichenko was looking through the sight on her rifle.

As the youngest partisan flighting the Nazi-allied Bulgarian monarchy, she became known as “the Amazon”.

She went on to become a scientist and global women’s activist. Ghodsee was able to meet and interview her, providing a living link for the author to the other women she writes about.

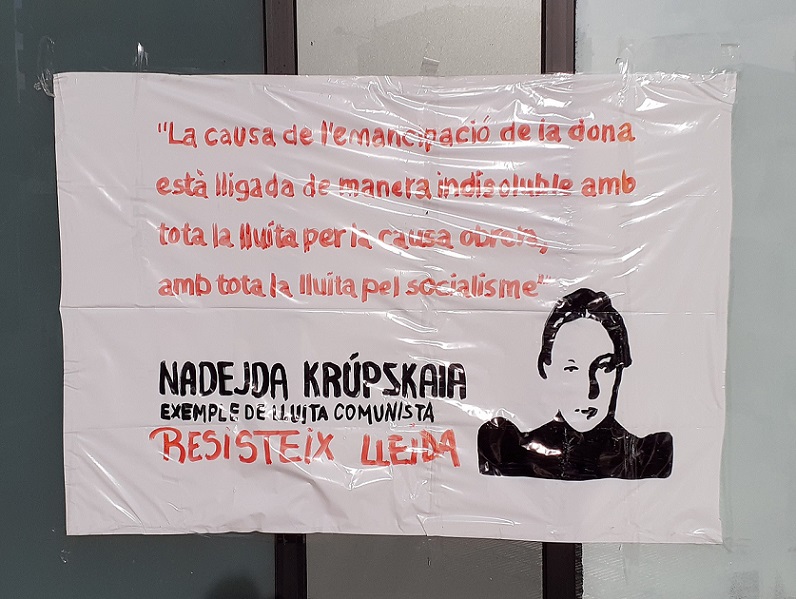

Any account of Russia’s October Revolution in 1917 and its aftermath should reference the troika of women at the heart of “Red Valkyries”: Alexandra Kollontai, Nadezhda Krupskaya and Inessa Armand. They knew and respected each other, all of them collaborated with Lenin (Krupskaya was his wife) and Armand may at one stage have been his lover.

Kollontai was a burning star of a feminist communism who opposed the Bolshevik’s centralized control. Her reforms overturned the status of women as the property of fathers and husbands, fostered a network of communally run children’s centres and freed up divorce from the shackles of the church. Politically isolated after Lenin’s death, her revolutionary legislation was gradually watered down.

Krupskaya was quick to realise that a socialist state required changes to the system of education and she laboured hard to organize adult literacy classes; worked on large scale and radical educational reform after October; managed her marriage’s domestic affairs and acted as Lenin’s secretary. Inessa Armand, who was a close friend, worked tirelessly for Lenin and her early death left him devastated.

The five women’s strength of soul, their emphatic faith and dedication to bettering life for ordinary people makes them compelling figures in the history of feminist socialism.

“Red Valkyries”, by Kristen Ghodsee, is published by Verso Books.

.jpg)