Sulaiman Addonia, the author of “Silence is my mother tongue”, had to flee Eritrea with his mother and siblings to a refugee camp in Sudan when he was a child.

Sean Sheehan

Sean Sheehan

This is the plight of the central characters in his novel – Saba, her older brother Hagos and their mother – and it adds another level of authenticity to his tale of refugee life that he crafts around them.

Saba struggles with authority figures within her exiled community – the midwife, the judge, the committee of elders, her mother – and sexuality becomes a prism for her conflicts with those who seek to impose their will, their cultural traditions and, in the larger world, their politics: But for Eritrean-Ethiopian Saba, “half from an occupied country and the other half from the occupying, the conflict was ongoing.”

Saba was studying hard in school, working towards her ambition to become a doctor, when her new life a school-less refugee camp puts everything on hold.

Determined not to give up on her dream, she also has to contend with the misunderstanding by others of her close relationship with her mute brother.

Their solicitude for one another transcends the need for spoken language, and it allows them to be comfortable with the way their gender roles are reversed.

Their solicitude for one another transcends the need for spoken language, and it allows them to be comfortable with the way their gender roles are reversed.

Hagos likes to do all the cooking and takes far more interest in clothes, hairstyles and makeup than his sister. Saba could be described as feisty, a convenient label for men to use when faced with spirited, independent-minded females.

The untoward exchange of masculinity and femininity between Saba and Hagos is seen by some as transgressive, especially when the camp’s midwife mistakes the delicate intimacy of their rapport as evidence of an illicit sexual relationship.

A woman’s body becomes a violent battleground in the refugee camp: sexual mores, rigidly enforced by conservatives anxious to preserve the community’s cultural identity, are challenged. Saba’s masturbates almost as an act of defiance: “Like the flag of a free country, she planted pleasure on her assaulted body with her fingers.”

A woman’s body becomes a violent battleground in the refugee camp: sexual mores, rigidly enforced by conservatives anxious to preserve the community’s cultural identity, are challenged. Saba’s masturbates almost as an act of defiance: “Like the flag of a free country, she planted pleasure on her assaulted body with her fingers.”

Saba is not the only one pursuing a dream. The novel begins with Jamal, a young man who worked in a cinema in his pre-refugee life, who has strung up a large white sheet between wooden poles and cut a big square hole in its centre. He calls his makeshift theatre Cinema Silenziso and he organises performances: “The trouble was that I, like many, had brought into the illusion that the sheet was an actual screen and that everything inside it was a real film – scene after scene made in a faraway place.”

This need for illusion becomes a metaphor for the community’s need to believe that their lives are not permanently reduced to a refugee existence.

This need for illusion becomes a metaphor for the community’s need to believe that their lives are not permanently reduced to a refugee existence.

“Silence is my mother tongue” is a daring novel and it tells a touching and uplifting story about personal liberation in a desperate situation.

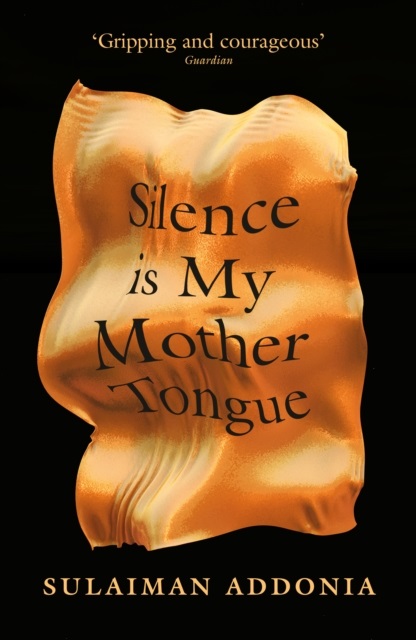

“Silence is my mother tongue”, by Sulaiman Addonia, is published by Indigo Press.

(Photos: Pixabay)

.jpg)