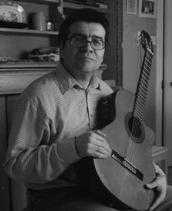

Born in 1948, in Santiago Chile, Carlos Arredondo arrived in Scotland 40 years ago as a political refugee from the Pinochet dictatorship. From his adopted country he has undertaken tireless solidarity work with Chile and Latin America.

Jordi Albacete

The 17 years of Pinochet dictatorship left behind thousands of murdered, missing and tortured people and almost a million political exiles. The exile has many faces and stories to tell.

In 1974 Carlos was 25-years-old and was one of the first groups of Chilean political exiles to arrive in Scotland.

When he arrived in Glasgow he was not a member of any political party, but he was a member of the Juventudes Obreras Católicas (JOC) [Catholic Youth Workers]. The Gallardo family, who were affiliated with JOC and almost all of his childhood friends were tortured and murdered. For them and for the many others, Carlos has dedicated his 39 years to activism, often through his music and poetry.

Carlos is a father, poet, singer-songwriter, lecturer, events organiser, but above all he is an historian of a chapter of Chilean history in which he is a protagonist. In his blog “Fabula” (For A Better Understanding of Latin America) and on his website he shares stories shaking with the emotion of the bloody dictatorship and the history of solidarity between Scotland and Chile. Carlos spoke to The Prisma.

What was arriving in Scotland like for you and the other exiles?

We arrived in 1974. There were about 40 of us. Most of us came from Peru, others from Argentina. Later many fellow Chileans arrived, many with their families, sometimes sponsored by trade unions or mining groups. Some had also left prisons and concentration camps.

We were welcomed there where Solidarity Committees had been formed, especially in the main cities like Glasgow, Edinburgh, Stirling, Dundee and Aberdeen. The solidarity groups were very curious to know about us, but especially about the missing and killed.

What was cultural integration like?

Chile is a culturally open country. We are a country of tea; we have it like the British as an afternoon refreshment.

Likewise, we are also reserved. We are like an island. We are separated from the rest of the continent by the Andes, the desert and the Antarctic. I don’t think that many of us suffered a great cultural shock. Fundamental to our integration was the fact that we always stayed very well organised.

Chile always had a democratic political culture where neighbourhood associations and sports clubs voted on any kind of decision. When we arrived in Scotland it was not a problem for us to get organised with the committees, with our duties and regulations, and that helped us a lot with integration.

How did Scottish solidarity work during the first years of exile?

How did Scottish solidarity work during the first years of exile?

During the dictatorship there was an event that perfectly illustrates to what extent a significant section of Scottish society was involved with what happened in Chile. Once, the British fighter-bomber engines, Hawker Hunters, were taken to be repaired at the Rolls-Royce factory in East Kilbride (near Glasgow). Chile had acquired the Hawker Hunters in 1967 and used them to bomb the La Moneda presidential palace on the 11th September 1973.

The factory workers went on strike so that the engines would not be repaired [some of them, like Bob Fulton, risked their jobs]. Eventually the protest resulted in the engines being returned to the Chilean air force without being repaired. In this boycott some Chilean and British “comrades” organised an act of support and gratitude for the Rolls-Royce comrades. I played in a recital.

Others have also been concerned about solidarity with revolutionary trials in Latin-American countries like Nicaragua and El Salvador. One of the exiles in Glasgow, an agricultural engineer, Manuel López, went to support agricultural projects managed by the Sandinistas in Nicaragua and was assassinated there by the Contra (counter-revolutionary movement supported by the CIA). In the 1978 football world cup in Argentina, Scotland organised a very strong boycott against the event.

Were there other important acts of support against the Pinochet regime?

Were there other important acts of support against the Pinochet regime?

Many important Labour politicians made political advancement through solidarity campaigns with Chile, both in Scotland and in England.

For example, the former British Prime Minister, Gordon Brown, attended an act of commemoration in Glasgow with me, for the 10 year anniversary of the Coup d’état.

How has solidarity in Scotland worked since the dictatorship?

With a lot of solidarity work; including the campaign for the Pinochet arrest and the lawsuit instigated by Judge Garzón for his trial.

We organised several cultural political events to remember 40years since the military coup. It was very surprised by the convening power that we had and I realised that Scottish solidarity has a very strong presence in Chile. Some Chileans were required for articles in some of the most widely-read newspapers in Scotland. Also, Chilean musicians in Scotland were invited to participate in BBC radio programmes.

What should not be forgotten?

What should not be forgotten?

I come from a very humble class in Chile. I grew up learning the importance of solidarity between neighbours. The family of the wife of my childhood friend Rolando Rodríguez Cordero, the Gallardo family, my friend, his wife, his brother-in-law, his brother-in-law’s wife and his father-in-law were all tortured and killed as punishment by the regime, simply for disagreeing with the dictatorship. All these years of my activism have been dedicated to them. I have never forgotten them.

The Prisma’ memoirs. June, 2014.

(Translated by Claire Donneky – Email: claire.donneky@ukgateway.net) – Photos: ixabay

.jpg)