“They call me a terrorist because I’m a Muslim. I’ve lost my temper a couple of times, which frustrates me because I end up getting into trouble. Some of my friends stand up for me but it isn’t enough. I want the teachers to do something, but they always tell me they’re really busy” (from a teenager’s statement to ChildLine).

Noelia Ceballos Terrén

Noelia Ceballos Terrén

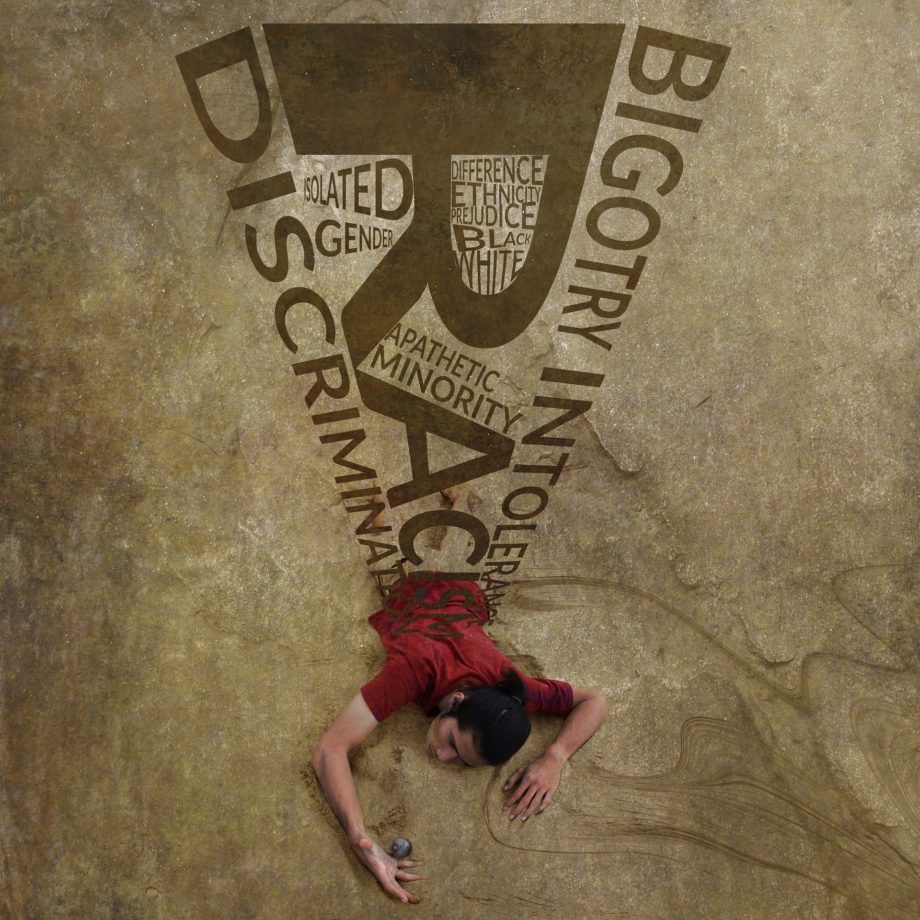

The school playground can turn into hell for many children. Educational centres are also the scene of racial discrimination.

Teachers don’t always assume a role of defending the attacked; awareness, time and information are lacking.

Language becomes the first act of aggression among classmates. The children of immigrants in the United Kingdom bear the label of ‘freshie’, a derogatory term for foreigners that leads them to believe that their origins make them different and inferior to the rest.

Despite the obligation that exists for schools to take anti-bullying measures, the reality is quite clear- more than 1400 children claimed to suffer from racist abuse in their schools in 2013, according to data compiled by the charity ChildLine. This figure shows an increase of 69% in comparison to the previous year.

Insults are based on racial stereotypes, which are repeated by children from a very early age. For this reason, young Muslim children can be called ‘terrorists’, or Somalians ‘pirates’. However, it would be a mistake to think that racism only comes from whites. As Professor Lola Okolosie explains in a column in The Guardian, the multicultural reality of many British schools is more complex, and many black and mixed-race children there replicate the same racist behaviour among themselves.

During her career, she has seen how Afro-Caribbean and African students mocked the facial features of others.

She also gives Bengali students as an example, who endured the taunts of their Pakistani classmates, who repeatedly said that they smelt of fish.

An anti-immigrant society

In this way, what is often seen as a joke by bullies is a dangerous reproduction of the general discrimination experienced by ethnic minorities in the UK.

According to some experts, such as Sue Minto, the Head of ChildLine, there is a correlation between the increasingly discriminatory and anti-immigrant government and media discourse, and the increase in racist incidents in schools.

According to some experts, such as Sue Minto, the Head of ChildLine, there is a correlation between the increasingly discriminatory and anti-immigrant government and media discourse, and the increase in racist incidents in schools.

In a statement to The Guardian, Minto claims that “there is greater focus on immigrants in the news…it’s a real talking point, and children aren’t oblivious to the conversations that go on around them…some are told to pack their bags and go back to their own countries, despite having been born in the United Kingdom”.

Fear and insecurity

Children from ethnic minorities can find themselves trapped in a cycle that starts with insults but can go much further. According to the organization Bullies Out, the harassment includes threats, humiliation, taunts and abusive emails, and classmates can be ignored, excluded from the group and have their belongings damaged, even going as far as physical violence.

The immediate effect of this psychological and physical violence is a great feeling of insecurity. According to Ditch the Label data, one out of ten bullied students attempted to commit suicide in 2013, and 30% of those who suffer some kind of bullying self-harm.

The Ditch the Label report also points to victims´ academic results. While 41% of students who weren’t bullied received the highest marks (A or A*), only 30% of those who were managed to reach the same level. In other words, racial discrimination can diminish the chances of those who suffer from it in their academic progress, essential for social integration.

The Ditch the Label report also points to victims´ academic results. While 41% of students who weren’t bullied received the highest marks (A or A*), only 30% of those who were managed to reach the same level. In other words, racial discrimination can diminish the chances of those who suffer from it in their academic progress, essential for social integration.

Liam Hackett, responsible for the Ditch the Label report, confirmed “the profound effect that bullying is having on students´ self-esteem and, therefore, the future prospects of millions of young people across the UK”.

But the problem doesn’t disappear when the victim leaves school. Anxiety, depression and behavioural problems can continue to appear throughout the life of an adult who was bullied as a child.

This is demonstrated by the study carried out by the professor of developmental psychology, Louise Arseneault, in which 50 year-old people still showed these symptoms despite the four decades that had gone by since the bitter experience.

The psychologist warns that bullying causes victims to be more exposed to unemployment and low incomes. They also find it harder to maintain relationships, have a social network and be satisfied with their lives.

These are all factors which, in the case of ethnic minorities, are added to an already less favourable situation with a greater risk of social exclusion than the rest.

Failing schools

Failing schools

The psychological support that a family can offer solves nothing if teaching staff have no anti-bullying policy in schools. This is an obligation that was introduced in the year 2000 as part of the Race Relations Act.

This doesn’t prevent there being continued silence surrounding racist bullying, primarily because the fear of retaliations for reporting it is a fundamental part of school abuse.

Sarah Soyei, a representative of the organization Show Racism the Red Card, offered an explanation in comments made to the BBC:

“Often teachers may not be aware of racism in their classrooms because victims are scared of reporting it out of fear of making the situation worse.”

However, once bullying comes to light, the educational institution does not always make the desired response. The majority of victims who turned to ChildLine in 2013 said that teachers ignored students who complained to them about the abuse they suffered, or took ineffective measures.

British teaching staff recognise this problem according to a survey carried out by Teachers TV, in which two thirds of teachers acknowledged that their schools had no effective anti-bullying policy, and 15% believed that racism had increased in their school. Specifically, one in five had known cases of Islamophobia in their classrooms.

The study also shows, albeit in a minority of case, that 2.6% of teachers had witnessed racist abuse from their colleagues towards students.

The study also shows, albeit in a minority of case, that 2.6% of teachers had witnessed racist abuse from their colleagues towards students.

Discriminatory system

Not only do ethnic minority students face racism from classmates, but their school lives are also marked by the British education system, which operates in a discriminatory way towards minorities according to some studies.

One such study reflects the greater harshness of school punishments on ethnic minority students compared with white students. The Department for Education and Skills claims that black students are three times more likely to be expelled from schools than others. In this way, the equality of opportunities that should be the foundation of our society is threatened from the first few years, when every child and teenager should be developing.

According to the same study, the lower expectations of teachers when it comes to black students are an expression of racism, and affect their academic results.

The curriculum poses another problem in a multicultural society such as Britain given that its content, and in particular its historical content, doesn’t represent all the cultures that make up classrooms. This contributes to a loss of interest and a feeling of abandonment in students, who see that their minority doesn’t receive recognition in the school.

That is the view of Sarah Pearce, a primary school teacher who shares her experience with the TES Connect newspaper.

That is the view of Sarah Pearce, a primary school teacher who shares her experience with the TES Connect newspaper.

She became aware of the discrimination contained within school textbooks when she had to teach a lesson on the Anglo-Saxons to a class composed of 90% Pakistani and Bengali students.

“They boycotted my class and there was nothing I could say. They had made the connection between History and identity and said “What is there about us?” At that moment I thought “this is crazy, the curriculum doesn’t attend to the needs of some communities”.

(The Prisma’ memoirs. July 2014)

(Translated by Alfie Lake) – Photos: Pixabay

.jpg)