Knowing what is going on between two people who are living together is fraught with difficulties per se and when the couple happen to be Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes, a relationship that ended with her suicide, the problem of secure knowledge reaches an impasse.

Sean Sheehan

We cannot step outside our mediation; we cannot, so to speak, stand on own shoulders and differentiate between what we see and what might really the case. There is a built-in limitation arising from being stuck with a particular horizon of meaning – and in the case of Plath and Hughes there is more than one horizon.

A memoir by the writer A. Alvarez, who knew Plath and was one of the first to recognize her poetic talent, established a viewpoint that became a familiar one: Plath was abandoned by a heartless man who mistreated and betrayed her.

“The pleasure of hearing ill of the dead is not a negligible one, but it pales between the pleasure of hearing ill of the living” – a lancing remark by Janet Malcolm that is characteristic of her superb examination of the conflicting interpretations and judgements surrounding Plath and Hughes.

Five biographies of Plath have now appeared and Malcolm finds Anne Stevenson’s “Bitter fame” to be the best of the lot – despite the way Ted Hughes and his sister Olwyn nobbled it to present their partial version of the truth. Complicating matters is Plath’s own ‘not-niceness’ that emerges in her “Ariel” poems and her novel “The bell jar” and, added to this, a slew of letters published by Mrs Plath from Sylvia to her mother that made the mother-daughter relationship seem part of Plath’s tragedy. A torrent of opinions and memoirs followed and Plath became an object of various post-mortems by those who knew or thought they knew her.

Another remark of Malcolm’s hits the spot: “One of the unpleasant but necessary conditions imposed on anyone writing about Sylvia Plath is a hardening of the heart against Ted Hughes”. This is a nice understatement. His destruction of Plath’s notebooks, written up to three days of her death, seems unforgiveable and his rationale – not wishing her children to have to read them – unconvincing. His wish to publish “The bell jar” in America, against the wishes of Mrs Plath, in order to generate cash to buy another house leaves a bad taste in the mouth. The fact that the woman he betrayed Plath for would later kill herself and the child they had is too awful to contemplate. Hughes emerges as so unlikeable that – although Malcolm doesn’t go so far as to say this – it becomes disconcerting to know that the poet Seamus Heaney could form a friendship with him.

Malcolm’s penetrating book raises the problem of writing about those who are unable to change how others perceive them. Plath remains a great poet and Ted and Olwyn Hughes remain two people most of us would not wish to know.

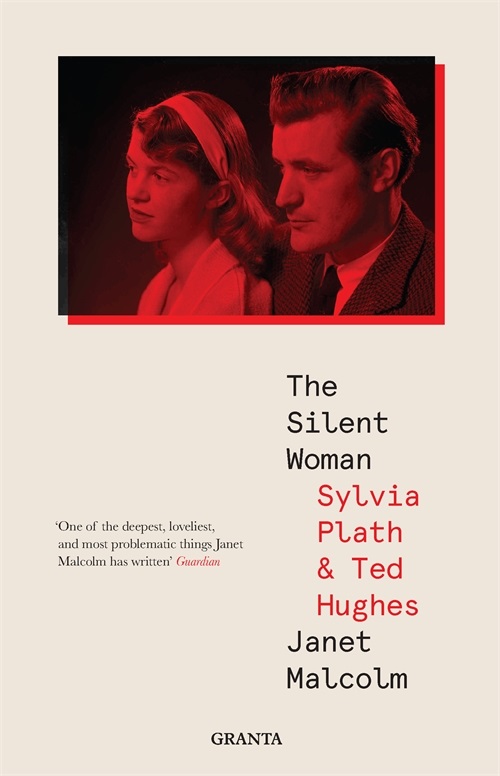

“The silent woman: Sylvia Plath & Ted Hughes”, by Janet Malcolm, is published by Granta.

.jpg)