Villa de Leyva is today a town full of people from the upper classes arriving from the capital and from other Colombian cities both within and outside the country, to enjoy the holidays, short getaways and weekends. The town is inhabited by wealthy owners of large mansions belonging to politicians, industrialists and soldiers, erected in the surrounding areas and hills.

Armando Orozco Tovar

Armando Orozco Tovar

In this region, as in many in Colombia, the colonial period is never far from the minds of the majority of its inhabitants: “Posada el virrey”, “Hotel la reina”, “Estadero Andalucía”, El marqués”, “El Príncipe”, “El conde”… Not one of these names refers to the region’s original inhabitants. The only evidence of a time before the Spanish is an ice-cream parlour with wooden sculptures and photographs of American Indians.

These names of colonial places appear all around the region in a multitude of establishments in order to welcome in tourists.

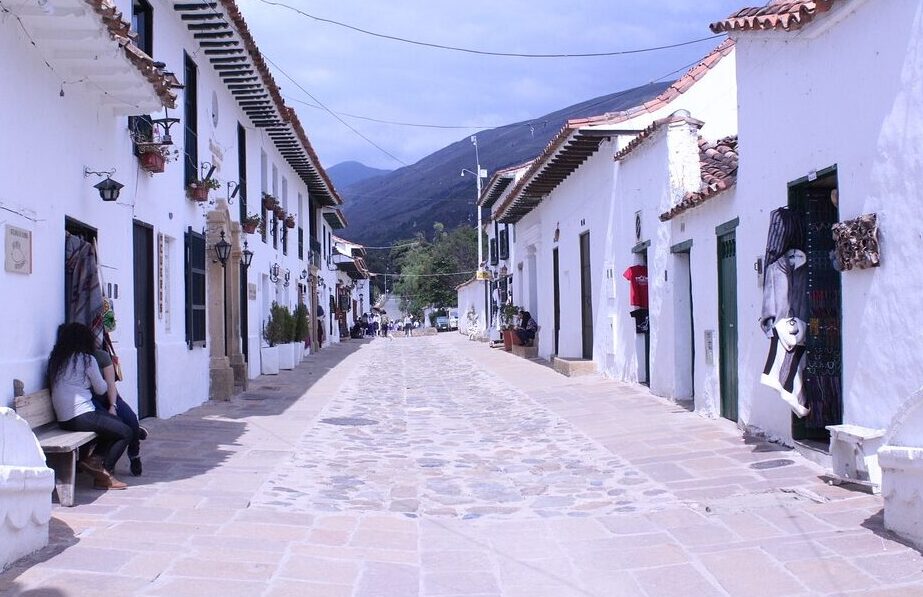

The names make reference to the Spanish presence from two hundred years earlier; as do the thick-walled white houses and high balconies,with many churches. There are, however, no monuments dedicated to Don Quijote.

The town in question is Villa de Leyva, situated five long hours to the North of Bogota, and founded by the Spaniard Andrés Venero de Leyva. I travelled there for the first time some years ago, before my daughter, María Fernanda, would later move there.

Today the town has become a giant metropolis with an enormous stone Plaza laid under the management of Ramón de Zubiría – an intellectual and writer from Cartagena – whilst he was the rector of the ‘Universidad de Los Andes’ in 1966. The Plaza has returned to its original state, which was once also the provisional Seat of Congress in the 19th century.

Today the town has become a giant metropolis with an enormous stone Plaza laid under the management of Ramón de Zubiría – an intellectual and writer from Cartagena – whilst he was the rector of the ‘Universidad de Los Andes’ in 1966. The Plaza has returned to its original state, which was once also the provisional Seat of Congress in the 19th century.

The area features cobblestone streets and various museums dedicated to colonial art. Villa de Leyva was the last home of Antonio Nariño, Precursor of the Independence of New Granada. Nariño came to the town to die, after being incarcerated, tortured and exiled many times in both the old and new world under the Spanish crown, just like the Venezuelan Francisco Miranda.

From ‘The Rights of Men and Citizens’ Nariño translated the principal declaration of the French Revolution of 1789, leading eventually, for him and his family, exile and all sorts of evil in the hands of the colonial authorities.

Villa de Leyva is today a town full of people from the upper classes arriving from the capital and from other cities both within and outside the country, to enjoy the holidays, short getaways and weekends. The town is inhabited by wealthy owners of large mansions belonging to politicians, industrialists and soldiers, erected in the surrounding areas and hills.

For the most part, visitors are young people here to get drunk; consequently leaving certain items in their wake: bottles, empty containers of all sorts of alcohol, soda bottles, plastic bags, condoms, cigarette butts… and certain herbs too.

For the most part, visitors are young people here to get drunk; consequently leaving certain items in their wake: bottles, empty containers of all sorts of alcohol, soda bottles, plastic bags, condoms, cigarette butts… and certain herbs too.

It’s amazing how the smell of urine is able to fill the air of the four corners of the Plaza; like some sort of animal ritual of marking one’s territory.

However, by some miracle of the Virgin Carmen – the town’s patroness – the colonial houses have not been demolished to make way for ugly meaningless boxes – representative of not one decent example of modern architecture – the sort that has befallen the majority of the country’s communities, including the country’s capital, Bogotá, and are a detriment to the cities’ historical and architectural heritage.

In one corner of the main square sits the museum house-workshop, which used to belong to Manuel Acuña – a painter of the‘Escuela Bachué’ school. It was a trend in the plastic arts, which, if art critic and writer Marta Traba, in the fifties,by chance did not arrive in the country, an aesthetic language which would still be dominating the arts today – one from which many artists – poor imitators of Rivera’s, Siqueiros’ and Orozco’s Mexican Muralism – did not want to depart.

Next to Manuel Acuña’s workshop lies the one belonging to José María Vargas Vila, who in 1885, the year of the war between the conservative and clerical programs of agrarian capital, was led by Rafael Núñez, author of the lyrics of the national anthem and of the growing financial capital with its liberal, freemason program.

Next to Manuel Acuña’s workshop lies the one belonging to José María Vargas Vila, who in 1885, the year of the war between the conservative and clerical programs of agrarian capital, was led by Rafael Núñez, author of the lyrics of the national anthem and of the growing financial capital with its liberal, freemason program.

Reading the inscription on its wall, it is here that the radical, anticlerical, liberal writer from Bogota wrote his text: El maestro. The countryside of Villa de Leyva is unparalleled, with a temperate climate that evokes never ending desire amongst artists, tycoons and owners of large fortunes as well as politicians, businessmen, generals, industrialists and publicists alike.

All, absolutely all of them are protected by the National Army which zealously takes care of them; silencing the protests by the country dwellers affected by the US-Colombia Free Trade Agreement (TLC), as we saw last year with the growers of potatoes and other products, in an unprecedented strike against the presidential king of the Nariño Palace. (The Prisma’s memoirs)

For María Fernanda Orozco and her son Manuel Perkuhn.

(Translated by Eleanor Gooch) – Photos: Pixabay

.jpg)