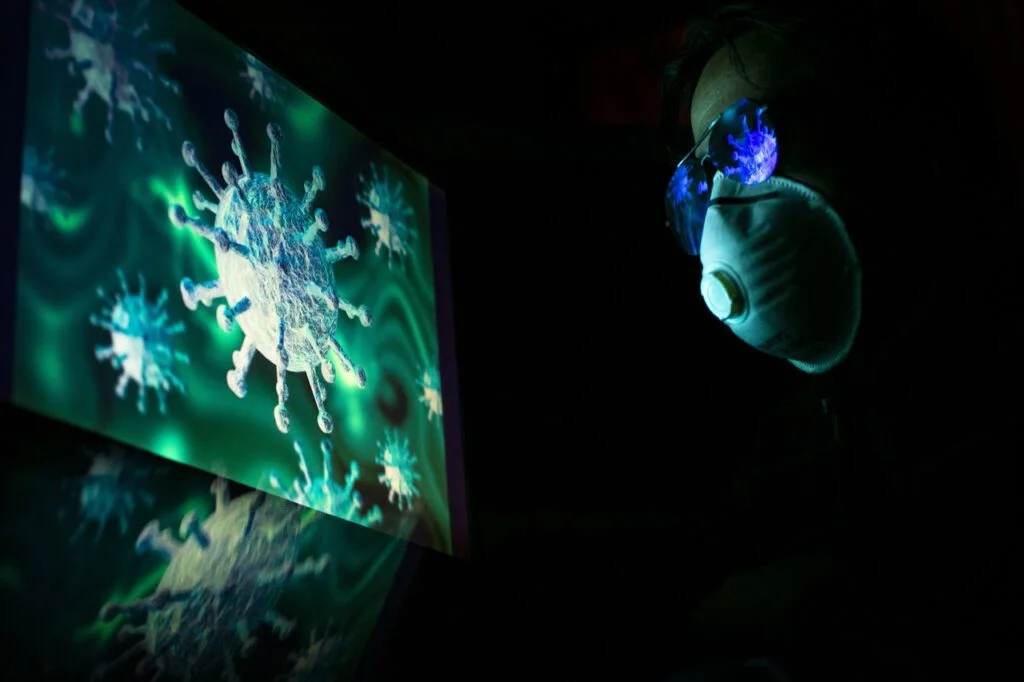

Following the lengthy lockdown forced upon us by Covid-19, which many have opted to continue, something in us changed – and social networks have a lot to answer for. We can no longer bear to live with difference, plurality or diversity. The pandemic forced us to isolate and coincided with exacerbated political polarisation.

Frei Betto

Frei Betto

Isolation did not necessarily equal solitary confinement, but only because we kept some windows open – digital networks, for example.

Yet political polarisation erupted into the sphere of emotion (rather than reason), with a marked difference from the polarisations of the past, in which debates centred on the ideas of enlightened authors (Marx, Smith, Gramsci, Keynes, Lenin, Arendt, etc.) and considered proposals for humanity’s future. Today, in place of meetings, projects or proposals, we have disputes – intensified by hatred, defamation, slurs and, ultimately, violence. Opponents are seen as the enemy. Rather than feeling the need to convince them, we seek to defeat them. Even going as far as virtual (and in some cases literal) assassination.

What has lowered us to this level of dehumanisation? Why have so many family and friendship ties been severed? Why has debate given way to hatred, exclusion and nullification?

Many responses and hypotheses have been proffered in response to these questions, one being that our psychological dependence on digital networks has destroyed our social bonds. More than 5 billion of the world’s 8 billion people are now connected to the internet.

Brazil, for example, ranks fifth worldwide in terms of users; in fact, there are more smartphones (249 million) than people (203 million) in the country.

Brazil, for example, ranks fifth worldwide in terms of users; in fact, there are more smartphones (249 million) than people (203 million) in the country.

The bubbles through which we experience the world are swallowing us up, exacerbating our individualism and narcissism. We are spectators of our own lives. We open digital tools like someone raising a theatre curtain or a veil covering a mirror. It is ourselves we want to see – our interest in others is limited to their value as an audience for our content. And if they express any disagreement with the content we publish, we can subject them to all kinds of aggressions or simply silence them by deleting them. We can no longer bear to live with difference, plurality or diversity.

This being the case, why would millions of network users vote for tolerant and democratic candidates? They prefer those created in their own image: irritable, sectarian and violent. Men and women do not give a hoot about democratic debate – they are entrenched in their certainty, even when challenged to prove it.

We have been lured by these networks, like fish attracted by succulent bait! They drain our time and mental energy. They heighten our anxiety. They demand all our attention. And then they implore us to pick a side on every issue.

We applaud anything that reinforces our point of view and demonise those who think differently. No exit: it is as if we are locked in one of those laboratory boxes for mice conditioned to perform automated reactions. We react by instinct, not by logic.

We applaud anything that reinforces our point of view and demonise those who think differently. No exit: it is as if we are locked in one of those laboratory boxes for mice conditioned to perform automated reactions. We react by instinct, not by logic.

The most fashionable illness today is stress. Mesmerised by the smartphone, we cannot bear to put it down, even at the dinner table, at a religious service, at work or on the move. We “sleep” with it switched on, because having it turned off is almost a form of self-imposed exile. If television is the extension of our eyes, and radio of our ears, then the mobile phone is the extension of our very being. The feeling of belonging to a tribe salves our loneliness, even if our relationships are merely virtual. And digital networks raise serious ethical challenges, including free access to pornography, sites encouraging terrorism and neo-Nazism, breach of family and personal privacy, cybercrime, and so on.

There is no need to be against technological innovation. We must even recognise that digital networks have many positive aspects, such as democratising information (despite fake news), breaking the monopoly of the mass media machines, enabling contact between people, sharing ideas and proposals, providing online courses and access to works of art, and speeding up research (Google processes more than 9 billion searches a day, and Brazil as a nation is among the top-five users).

But we must remain vigilant: regulatory frameworks for digital platforms need to be created in order to perfect democracy. As Eugênio Bucci points out in his excellent book Incerteza, um ensaio (Autêntica, 2023): “In totalitarianism the core of the state is totally opaque and shielded, while personal privacy is transparent and vulnerable (to power). Now, change the word ‘state’ for the compound word ‘technological-capital’ and you will have a reliable portrait of our time. We are merely observed, watched, scrutinised, inspected and capitalised beings in the world’s spectacle.”

But we must remain vigilant: regulatory frameworks for digital platforms need to be created in order to perfect democracy. As Eugênio Bucci points out in his excellent book Incerteza, um ensaio (Autêntica, 2023): “In totalitarianism the core of the state is totally opaque and shielded, while personal privacy is transparent and vulnerable (to power). Now, change the word ‘state’ for the compound word ‘technological-capital’ and you will have a reliable portrait of our time. We are merely observed, watched, scrutinised, inspected and capitalised beings in the world’s spectacle.”

(Translated by Rebecca Ndhlovu – rebeccandhlovu@hotmail.co.uk) – Photos: Pixabay

.jpg)