We feel an enormous emptiness when we lose a friend. An emptiness which fills with anguish, and overflows with anger when we discover in the empty spaces of our lives that the time we should have given to our lost friend has slipped away.

José Machado Pais

José Machado Pais

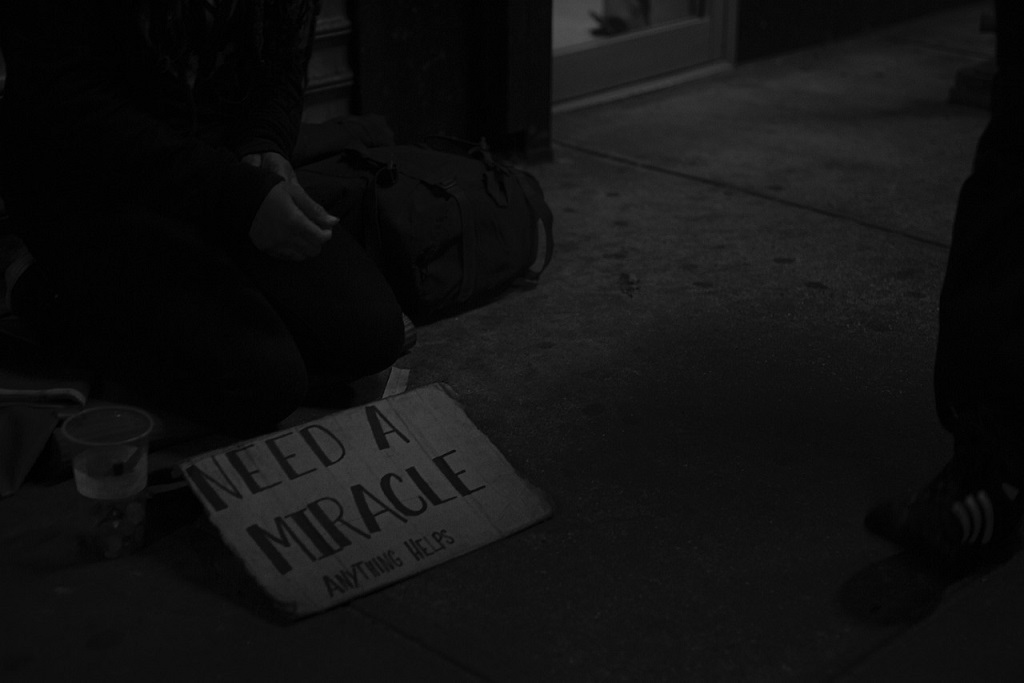

This disturbing feeling assails me when I take account of the death of Jose. He was sometimes viewed as a vagabond, a drunk, a madman…. But none of that! He was just a homeless man.

However, in the dominant social imagery the homeless pay the price for not fitting in to the world, seen as dirty – social rubbish. The common view ignores the misery that surrounds them, even as a way to protect ourselves from feeling guilty. I met Jose sitting on the steps at the entrance to the church of São João de Deus in Lisbon. He was reading the bible. I learned a lot from Jose. For example, the value of communication, the importance of the word for understanding the mystery of life.

Jose explained to me that when we speak it is because we are, and if we are it is because we are alive, or we are living because we exist. In the same way that we give life to words, words also give us life, an identity of our own, and awareness of our existence. It is what happens, when for example, we are identified by a name.

When someone called him by his name, Jose lit up. In his homeless condition he didn’t complain about having nothing, he just didn’t want to lose his name.

“Look at old Ze the beard!. That doesn’t bother me! What I want is that people call me Jose! And that they don’t call me filthy!” When someone called him by his name, Jose assumed an identity that allowed him to attach meaning to his precarious existence. Recognising someone’s name is equivalent to recognising them as a person, an individual.

“Look at old Ze the beard!. That doesn’t bother me! What I want is that people call me Jose! And that they don’t call me filthy!” When someone called him by his name, Jose assumed an identity that allowed him to attach meaning to his precarious existence. Recognising someone’s name is equivalent to recognising them as a person, an individual.

I met you while I was writing a book about solitude (On the traces of loneliness). I read a lot of specialised literature on the subject. But your thoughts, Jose, were my main source of inspiration. On one occasion you said to me: “Loneliness is a feeling that people have in their heart. It is inside us, what matters is to really feel it, not just to express it in words, but to feel it within ourselves, inside what we are”. I went home pondering over what you said.

How does one reach the reality of this feeling which is not expressed in words, but is just felt? It is a challenge to which the social sciences have evaded, to the same extent that feelings slip away from the methods which are usually employed to describe other kinds of realities besides feelings.

We know how to crack a nut and extract the kernel. We know how to open a tin of tuna. We know how to open a safe, or even to break into one.

But as you told me Jose, it is very difficult to reach the feelings of a person, to get inside that little emotional box which is part of our existence.

But as you told me Jose, it is very difficult to reach the feelings of a person, to get inside that little emotional box which is part of our existence.

What kind of key will decipher the enigma of loneliness? Merleau-Ponty wrote a book (“The eye and the mind”), where he talked about his liking for those painters that said things looked at them when they were paining them. That is what is missing. To feel the look of those who, in their loneliness, are looked away from or simply ignored. This implies a method. An inward look. To look into what is normally despised, but also a look which is committed, that is one involving a commitment, an obligation to denounce, to uncover, to unravel, to listen, of giving. As a friend of yours from the street once said to me: “sometimes a word is worth more than a coin”.

I haven’t forgotten that feeling of gratitude that gleamed in your eye when someone greeted you.

On one occasion I gave him a jacket that I didn’t use. Afterwards I envied my old jacket for the intimate relation it had with the homeless person. I regret that I could never write a biography of the new life of my old jacket, so as to discover its new identity, and above all the identity of the person who wore it.

Do you remember, Jose, our walks through our dear Lisbon? Together we put into practice a method of research, the method of (passeiologia) strolling-study. Walking through the streets on foot, we allowed ourselves to be carried along more by the feeling of what we were discovering, than by the motion of our shoes.

Do you remember, Jose, our walks through our dear Lisbon? Together we put into practice a method of research, the method of (passeiologia) strolling-study. Walking through the streets on foot, we allowed ourselves to be carried along more by the feeling of what we were discovering, than by the motion of our shoes.

We were like two angels out of Wim Wenders film “Wings of desire”, wandering, invisible, through the secrets of the urban labyrinths. In my book “Nos rastos solidão”, I made you a dedication: “To Jose, philosopher of the street, vagabond prophet, with whom I learned how to stroll through the world. The last time we met you were upset. By giving a smile and holding out your hand, a rain hat ruined your bag of bread. You knew that they were taking you into hospital again. In the morning I look for you. In the traces of loneliness.”

When I went to find you in the psychiatric clinic of the Julio de Matos Hospital, I didn’t recognize you. They had shaved your beard and your head. Stupidly, I didn’t know how to interpret the gleam in your eye. It was only when you came slowly towards me and gave me a hug.

One day you said to me “Destiny has many whims, it depends on the will of each of us”.

If I had properly valued your thoughts, the wisdom of your street philosophy, I would not today be feeling an immense anger with myself.

If I had properly valued your thoughts, the wisdom of your street philosophy, I would not today be feeling an immense anger with myself.

But no, I wasn’t capable of discovering that will to disarm the whims of destiny. So I feel I betrayed our friendship when, for example, I left you in the street, handed you over to yourself, to your loneliness. You don’t leave a friend in the street. How it weighs on my conscience now.

Thank you for those very valuable lessons in life which you gave me. With you I learned that loneliness is a failure to meet. A disconnection with the other – in some cases, a disconnection with ourselves. Each of us is presupposes the existence of others, even of others that exist within us and tie us together in their conflicts. How can we reach the other that exists, inside or outside of ourselves? How can we cross the distance that divides us?

In the cemetery in Alcabideche, in a square of earth, where your body lies, there is a stone which holds your words: “I like to wear earth on my feet, to forget the weariness of my shoes”. (The Prisma’s memoirs)

(Translated by Graham Douglas) – Photos: Pixabay

.jpg)