The Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) in the 1980s and the pro-Palestine movement have both faced intense scrutiny and demonization. Despite operating in different contexts, both share common strategies and challenges in countering negative portrayals. Understanding how the CND operated can provide a roadmap for the progressive movements of today.

Harry Allen

As the Palestinian struggle spills onto to the streets of London, a targeted assault by high-profile political figures seems to be underway to bludgeon the spirit of protestors and peace advocates.

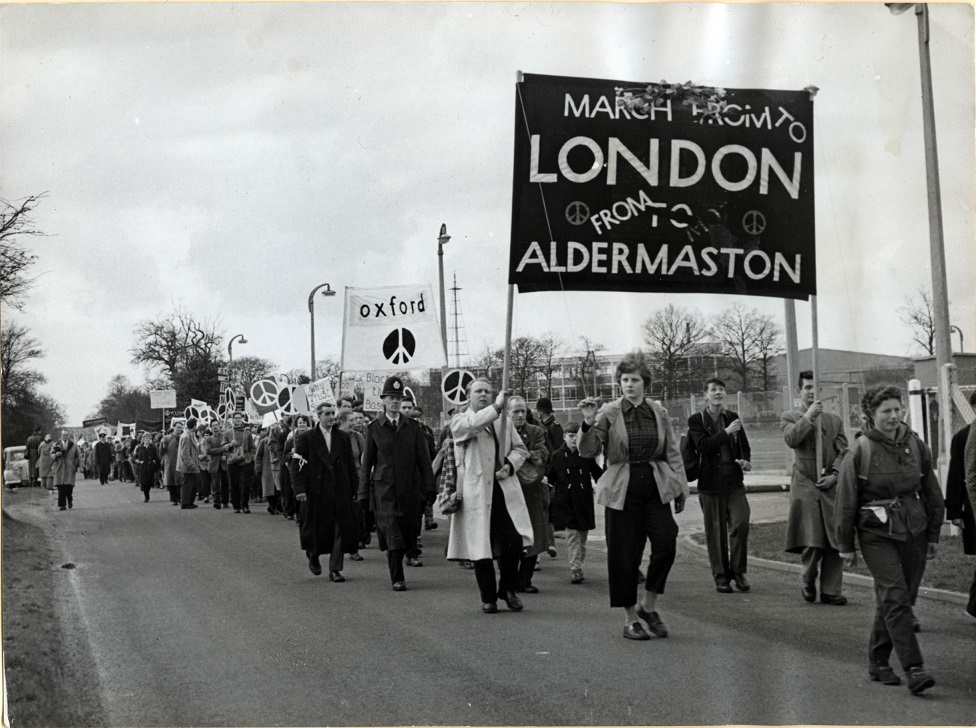

Something similar happened in the 1980s when CND faced the same reaction under the Thatcher and Reagan governments, who were fixated on the arms race. Amidst a growing fear of nuclear annihilation, Britain was purchasing its nuclear trident submarines, whilst the United States, keen to win the Cold War, began stockpiling and positioning nuclear launch pads across NATO states, including in Britain itself.

British intellectuals spearheaded the creation of the CND in 1958 against the growing threat of nuclear escalation. Whether war was a close reality, is another question entirely, but it drew a vast intersection of society in favour of a singular goal for peace.

The pro-Palestinian movement has its roots in early 20th-century struggles against an increasingly aggressive Israeli government and settler movement. A singular goal, but with arguably more global appeal.

A YouGov poll conducted in May 2024 found that 73% of people support an immediate ceasefire in Gaza indicating a growing majority of society against Israel’s continued genocide that has since seen 36,400 people killed so far.

The CND’s national membership grew from 4,267 to 90,000, and local membership increased to 250,000 between 1979 and 1984, suggesting substantial support for CND’s goals at the height of tensions.

Political rhetoric and varying perceptions

Its left-leaning political slant made it susceptible to attacks from the right across Britain and the U.S.

British PM Margaret Thatcher even said, “Those who press for unilateral disarmament in the West risk laying the free world open to blackmail, and even to enslavement.” In a similarly-styled outcry in April 2024, Israeli PM Benjamin Netanyahu described anti-genocide campus protests as “horrific” and “antisemitic,” comparing them to the 1930’s in Germany.

Thatcher sought to conflate the desire for peace with a wish for surrender, whilst Netanyahu finds himself using antisemitism as a political cover for land grabs in Gaza and the West Bank.

It is no secret the CND suffered from the same far-left labelling that similarly brands pro-Palestine protests as “hate marches,” with CND equally described by Thatcher as the “enemy within” in a 1984 House of Commons speech.

“[The] CND lost the argument in the 80s,” one BBC interviewee, Jonathan, claimed in 2006, “The victory over Communism would not have occurred if the British people had accepted their nonsense.”

Much can be said for the victory over communism in 1989, but most analysis rests on soviet economic decline as opposed to nuclear positioning.

Much can be said for the victory over communism in 1989, but most analysis rests on soviet economic decline as opposed to nuclear positioning.

Strong media rebuttals led to more CND support during the CND’s heyday with one Guardian columnist saying in retrospect “it appear[ed] that CND’s support was strongest when its arguments were weakest.”

Membership fell to 15,000 at the turn of the 20th century when the Cold War was well and truly put on ice. The group has struggled to gather the same momentum since. Pro-Palestinian movements have similarly had a reactive support level of support, with public desire for a ceasefire at 66% in February, up from 59% in a YouGov November poll, markedly increasing as bombardment on Gaza has intensified.

When the U.S. deployed nuclear weapons on British soil in the 1980’s, or when Israel attacked Gaza in 2014, popular support comes to a boiling point, at least in the polls, then tapers off.

Successes and failures of the CND

It is argued that neither group has so far achieved their specific goals despite overwhelming support at their peak, but the unseen quality to these protests is that effects are not felt until popular sentiment dies down.

Former Private Secretary to the UK Defence Minister, Sir Richard Mottram said the “[CND] contributed to the sense of validity…in [Britain] pursuing the arms control dimension” leading to the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces treaty in 1987, and the final removal of US cruise missiles from Greenham Common in 1991.

Former Private Secretary to the UK Defence Minister, Sir Richard Mottram said the “[CND] contributed to the sense of validity…in [Britain] pursuing the arms control dimension” leading to the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces treaty in 1987, and the final removal of US cruise missiles from Greenham Common in 1991.

Despite the war of words and claims by academic Dr Anthony Glees that the CND were “useful idiots” of the Soviet Union, it was apparent that they contributed to a changing conversation around nuclear weapons. A perception of left-wing bias, similar to that of the pro-Palestine movement, undermined the CND’s ability to build a coalition among other political factions, but it didn’t stop their impact on government policy.

LSE Professor Mary Kaldor says the Zero Option was proposed by Reagan’s advisor to get rid of all intermediate-range weapons in Europe. She claims CND banners played their part in the adoption of this policy.

In an act of adoption, the 80’s Labour Party adopted unilateral disarmament eventually, although the policy only lasted until it’s abandonment in 1989. Political pressure seems to be the key component to the CND’s relative successes.

Looking back on history

Looking back on history

Pro-Palestinian movements could be similarly praised for their pressure on the Biden administration to adopt a stronger stance on Israel.

The “Abandon Biden” movement is gathering momentum, but the impact on the ceasefire agreement is difficult to measure, and remains so.

A “right to defence” characterises both the pro-nuclear argument, and the Israeli argument following October 7th – but a key difference lies in theory and practicality.

“A world without nuclear weapons would be less stable and more dangerous for all of us.” Margaret Thatcher proclaimed in a desire for weapons to stay and be stationed, on British soil. The CND were fighting against a theoretical vision of nuclear conflict, whilst Israel has already committed its atrocities. Pre-emptive action is clearly more effective. Palestinian movements, however, are fighting a historical set of grievances, and this wherein the difficulty lies in assessing how effective the movement has been so far.

Funding and finance

According to Declassified UK 40% of Kier Starmer’s shadow cabinet are funded by the Israel lobby, and over 120 Conservative MPs the same.

The CND relied only on grassroots financial support, limiting its scope for direct policy action, while the pro-Palestine movement is similar, lacking a coordinated direct method for lobbying MP’s.

Palestinian Solidarity Campaign and Medical Aid for Palestinians, two of the biggest action groups, both focus more intensely on media coverage, education and conflict monitoring.

Palestinian Solidarity Campaign and Medical Aid for Palestinians, two of the biggest action groups, both focus more intensely on media coverage, education and conflict monitoring.

In many cases the playing field is unequal on a parliamentary level, where all-expenses paid trips to Israel are clearly swaying our representative’s objectivity on the issue.

The Israel lobby has cemented itself into the UK political system in a way that neither the CND nor Pro-Palestine movement have been able to do. If making noise was enough for the CND’s minor successes, it may not necessarily be enough for the Pro-Palestinian movement. A more systematic approach will be needed.

(Photos: Pixabay)

.jpg)