These are the stories of people convicted of minor crimes and deported to their place of birth in the Azores, which many left as young children. Deported hours after sentences completed, refused permission to say goodbye to families, or refused entry after a holiday, all because they didn’t apply for citizenship decades earlier. How the ‘most advanced country in the world’ treats those who can’t fight back.

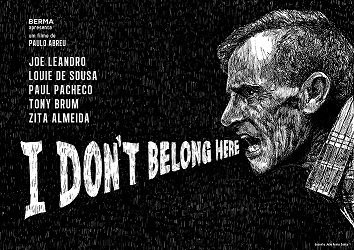

Paulo Abreu’s film (75 mins), which premiered at the DocLisboa Film Festival in Lisbon, tells the story of people who were thrown out of the US and Canada, and dumped where they were born on the Portuguese islands of the Azores, due to not having claimed citizenship.

A change in US law in 1996 made any non-US citizen sentenced to more than 1 year in jail or probation, for crimes of ‘moral turpitude’ liable to deportation. And it is retro-active.

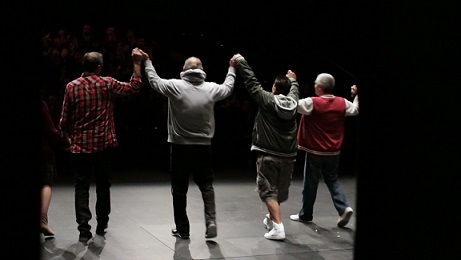

The actors are playing themselves and the film was made on a very low budget, at the same time as a play, which has been put on at many theatres in Portugal.

Everyone sees it as an educational project – after living legally for decades in the US or Canada without realising it was important to apply for citizenship, a relatively minor conviction can lead to families being broken up – and for what benefit? Many of them feel they have been given another sentence after having served one in North America.

Despite their situation, they’ve kept a sense of humour, Tony offers a free performance for the Queen if they come to the UK.

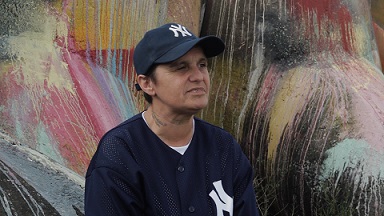

The Prisma talked to the director of the film Paulo Abreu, and the play Dinarte Branco, and four of the actors who played themselves, Tony, Louie, Paul and Zita.

How did the film and the play happen?

Paulo: We began shooting in the Azores with just the camera,.

I was only paid to make videos, not a film, and this one is a departure from my previous experimental work, however the only part that was not reality was when Paul dies and merges into the scenario.

Tony: Nathalie Mansoux made a documentary, Deported, in 2012, but then Dinarte took it in the direction of a play. She and I talked about bringing this to the people: “Look, if you screw up this can happen to you”. Dinarte selected actors and we all became part of it.

Dinarte. Observatorio dos Luso Descendentes is an NGO run by Paulo Fontes, which works with Portuguese people all over the world, and the president told me in 2013 what is happening in the Azores. I thought a play would be a good idea, but because Paulo’s video material was so good, we decided to do a film at the same time.

How did it happen to you?

Tony: After 911, I was in the contracting business and everyone thought we were going to war, so I thought I’d go back to the Azores for a holiday, fix up a house and retire.

The US thought they’d save some of the money they were spending on homeland security by shipping out as many people as they could.

Louie: Everybody has their own stories. I served in the US army for 7 years, you can die for your country. I broke the law and I served my time. When I enlisted they told me “You’ll get citizenship, don’t worry about it”. So, when I’d done my time, I thought I was going home, but no, “the immigration wants to talk to you”. I’m doing another life sentence. What did that 7 years in the army count for? They used me.

Do you feel you represent the other deportees?

Louie: We are also trying to do something political, in the US and here: deportation starts with one country, but the other has to accept. If Portugal had looked at the situation, and seen that some people have been out of the country since they were young kids and don’t speak Portuguese, they should have said ‘no’ in those cases.

Tony: Portugal already agreed that foreigners who commit serious crimes in Portugal can be deported, so they had to take us. Castro was cool. When Cubans were jailed in the US, Castro wouldn’t take them back, he said “you accepted them, you own them”. Remember years ago, he opened up the jails and the insane asylums and told them, “You want to go to America, off you go!” The movie Scarface was made out of that time.

In the film we can see the huge effect that deportation has on families.

In the film we can see the huge effect that deportation has on families.

Tony: It’s a double punishment the family pays as well as the offender. We are going to pay for the rest of our lives.

We can go back to visit, but what’s the point? If I was younger, I would go, and then the chase would be on!

There were scenes in court, the wife saying: “Don’t take my husband, I love him!.” “Sorry”, says the judge: “you fit the category, you are gone”.

Being in the film, was it therapeutic?

Being in the film, was it therapeutic?

Tony: You got a soul, we all got souls, yeah? It’s a mutual thing, we all feel it. But nobody knows, what it’s like till they stand in our shoes, ya got it?

Louie: It’s different for each person. For me it’s my son, my daughter, my grandkids. My mom and dad passed away. I got 2 brothers over there. We all created a family here – but where’s our true hearts? If Tony leaves, we’ll miss him, but my family – they hurt every day, so do I. Christmas and New Year.

Have you come to terms with your pasts?

Tony: When you’re young it’s sex, drugs and rock ‘n’ roll. We all have one gene in us, that we never feel good enough, I want better! That’s the gene that kills us – when the want outweighs the need, you’re done. Mick Jagger should said that!

You said you enjoy the Azores, while everyone else hates it.

Paul: For the previous 25 years I was high or drunk, so by the time the deportation happened, my family had had enough of me, I needed a change, otherwise I was going to die. Jail’s not for me, the idea of somebody telling me when to get up and go to bed, it’s not for humans, it doesn’t work. Put a young person in jail, and they learn how to steal cars.

Every rehab I went for, never worked for me. I’ve got grown-up kids in Canada, but I can’t keep running and hiding to stay there. So, I took my chances.

for, never worked for me. I’ve got grown-up kids in Canada, but I can’t keep running and hiding to stay there. So, I took my chances.

When I got here I was petrified, I didn’t know what to do. OLD picked me up.

No snow is perfect, rain – I can live with. I was going to say you don’t need to shower every day – but no, you should!

Where is the film going now?

Dinarte: We’re trying to raise money. We need to sell the film to RTP, and we have to pay for colour correction.

There are people in Canada and the US, who are concerned with these issues. We can apply for special authorisation for all of us to go. We will take it to festivals, and return to the places where we put the play on.

There are people in Canada and the US, who are concerned with these issues. We can apply for special authorisation for all of us to go. We will take it to festivals, and return to the places where we put the play on.

We should also work with schools with the film.

Tony: After the film, kids came up to me, and said they didn’t know, so they see things differently now.

Zita, you haven’t said anything.

I’m tired! I think the deportation is never going to stop. Separating families is heartbreaking. You’re taking the love from the family. We just have the internet. My friends think we’re in paradise. To me it’s a jail.

(Stills by permission of the director Paulo Abreu)

.jpg)