He left Uruguay in 1974 at the age of 24, escaping the repression of the dictatorship, which had twice imprisoned him, setting him free for the second time, with his passport in his hand and the idea to set off for Europe in his head. To Paris to be exact, where some members of his family were living.

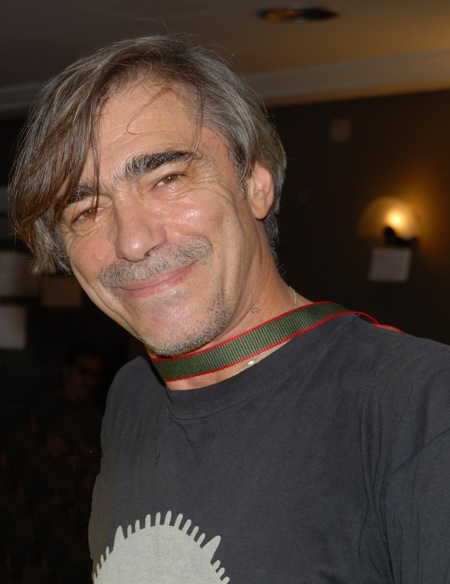

Juan Galbete

And he arrived there only to emigrate again, this time not so far as his previous journey, but to Newport (Wales) where he trained as a photo-journalist and then to London, an activity that since then he has practiced in different print media as a freelance for a number of NGO’s, TV channels, and newspapers like the Guardian or the Sunday Times, among other papers and magazines. And in 1992 he won first prize in the Nature category of the World Press Photo Prize.

At that time he was motivated by anger and maybe to some degree he still is today at the age of 73, although he would seem to have much less of it, after more than 50 years of work.

His political anxieties and his struggle since his time in university against what were then only “the preliminary manoeuvres of the dictatorship” before the Coup d’Etat of June 1973 in Uruguay, sowed the seeds of this anger that is still with him. And through trying to channel it as an activist at university, where he studied Humanities, he ended locked away in the cells of the military barracks in Montevideo. He was never found guilty of a crime or sentenced it is clear, so he decided to leave his country and head for Europe.

After arriving in London he learned about the dictatorship in Chile, through working with exiled Chilean support and solidarity groups, and documenting through his photographic work, the life of the Latin-American community in London, a community, which in his opinion “has changed a great deal” since he arrived in 1974.

“90 % of Latin Americans of that time were political exiles like me, and during the 80’s more people began to arrive for economic reasons, although I don’t like to make distinctions between political and economic exile.”

“As Mario Benedetti said: all exiles are political: they also leave because of a policy, an economic policy in this case, but a policy in the end, which did not allow them to grow as an individual and gave them no opportunities to work”, an opinion he shares.

It was during the 1980’s when he began to work with organizations like Amnesty International, and he returned to Uruguay to cover the 1984 elections which brought an end to the dictatorship.

Later he travelled to Chile for the National Plebiscite of 1988.

From everything he has done during his long career, one of the pieces of work which may have left the greatest mark on him was a journey he made to Burma and China at the end of 2009, during which he collected enough images to compile a photographic series titled “Burmese Days Revisited”.

It was “an allegory” explains Etchart, of the years that the British writer George Orwell spent in Burma as a member of the Imperial Police in Burma, which formed the basis for his book Burmese Days. Etchart’s work was inspired by the Orwell Prize, a literary prize conferred by British writers and publishers for political writing in the tradition of Orwell, and which the photographer is now trying to extend to the genre of photography.

His main purpose was to carry out a reportage reflecting the present political tensions between China “the empire” which dominates Burma today, compared to the experiences of Orwell as a subject of the British Empire, an imperialism which he later disowned.

The political difficulties in the country forced him to change his initial plan to a more descriptive work, comparing Chinese and Burmese customs “ a very beautiful culture, which in more than half a century has hardly changed” he points out.

His projects planned included a visit to the Green Line, the demarcation line which separates the Greek and Turkish communities in Nicosia, Cyprus, at the invitation of the British Council. It is true that something remains of all the anger which served him as a fuel when he was young, but “now the motivations are different”, he says with a youthful tone, given that for example, since the 1990’s he has been covering less conflicts in order to concentrate on cultural themes.

“When you are at that age you have different concerns, some existential anxieties and anger, of course, although I still have this feeling to a degree, about what is happening now in North Africa and towards the hypocrisies of Western governments.”

(Translated by Graham Douglas) – The photos in are by Julio Etchart and authorised by the author for publication)

.jpg)