Before the street, people who were not family socialised in a village square, a town’s marketplace or, strictly for the elite, a court or castle.

Sean Sheehan

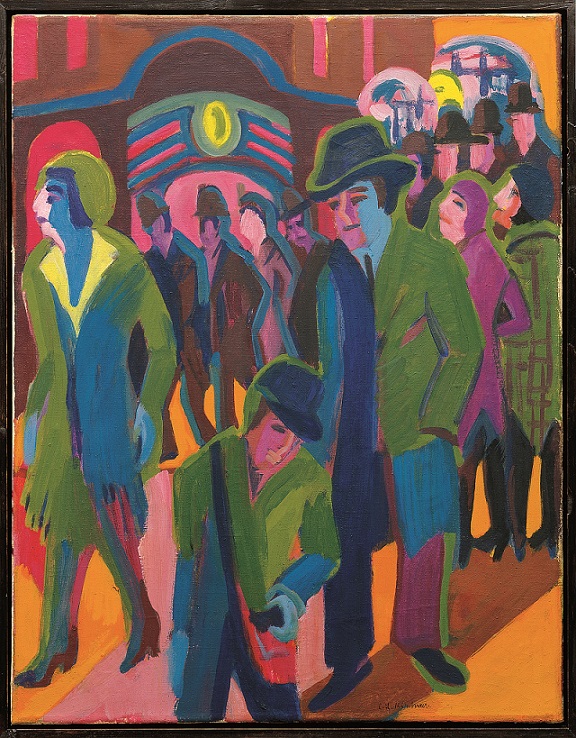

Streets as we know them came with industrialisation, becoming a vital public space and by the early 20th century street life was the subject matter of art forms old and new: not just painting but also photography and film.

The public and the private co-existed on city streets, a peculiar symbiosis that made the street the locus of activities as different as shopping and protesting but also a private place for the contemplative walker; a public stage and a private retreat.

“Street life” tracks the various ways artists have engaged with the importance of the street in modern society. Photography, the focus of two of the six chapters, comes to the fore after the opening chapter’s coverage of Futurists and Expressionists.

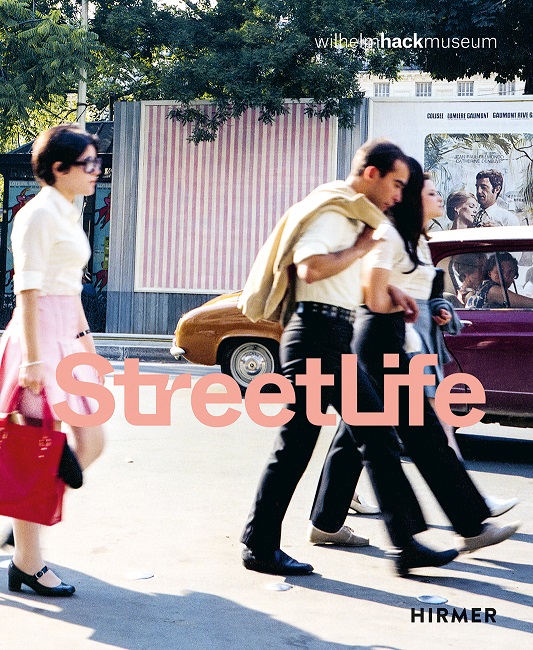

Street photography, emerging in the 1920s and ‘30s with hand-held cameras and the shortened exposure times that came with negative film instead of glass plates, transformed earlier pictorial art forms like still life and portraiture.

Photographers become fluent in reading streetscapes, freezing motion in the frame – a paradoxical kind of still life – and portraiture vacated the painter’s formal studio setting to be realised instead by momentarily arresting a person’s posture and face.

Such moments are so nondescript, writes one of the essayists, “that only the image itself makes them compelling”.

The historical approach continues in a later part of the book and extends the genealogy of street photography to include an emerging enthrallment with the built nature of streets and highways, their fabric, furniture and architecture.

The cult of the automobile shifted the axis of street photography as car parks, petrol stations and interchanges became of interest.

The visual presence of vehicles in daily and cultural life signalled a farewell to the street as predominantly a social space. Cars became the new citizens of the street, dictating urban planning and signage systems for topographies fuelled by oil.

The contemporary political and social anger of protestors has reclaimed the street as a place for bringing people together – the book’s final chapter looks at this – and at the same time there is a growing disenchantment with the automobile and its ascendancy over pedestrians.

The fascination of American street photographers of the 1970s and ‘80s for car-based street life now seems like a road to nowhere and there is a return to the street as a site for intervention by people.

Street life’s achievement is its alignment of street photography with artists in other disciplines responding to the same changes in urban culture over the last hundred years.

The book is packed with illustrations of the work of photographers, painters and other artists who have something important in common, backed up by informative essays by a knowledgeable team of contributors.

“Street life: The street in art from Kirchner to Streuli” is published by Hirmer.

(Photos supplied by the publisher)

.jpg)