History must not be erased we are told, when a slaver’s statue is taken down. Here a mythical history is still being created to preserve the happy colonial family image created during Salazar’s dictatorship. And education is schools still masks the reality of a brutal colonialism.

Graham Douglas

Graham Douglas

European colonialism officially ended during the last century, but the nostalgia for empire is slower to fade, and it was said to be a factor in Britain’s vote to leave the European Union.

Despite the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement, Black history education is a contested area in many countries. There are statutory requirements to teach it in schools in Brazil and the UK but not in Portugal, and there are growing attempts to prevent Black history being taught in US schools.

Portuguese colonialism abruptly ended with the Revolution in 1974, but left a unique legacy which Marta Pessoa explores in her latest film “Rosinha and other wild animals”. It won the Arvore da Vida (Tree of Life) award at the 20th Indielisboa film festival this month, where I spoke to her for The Prisma.

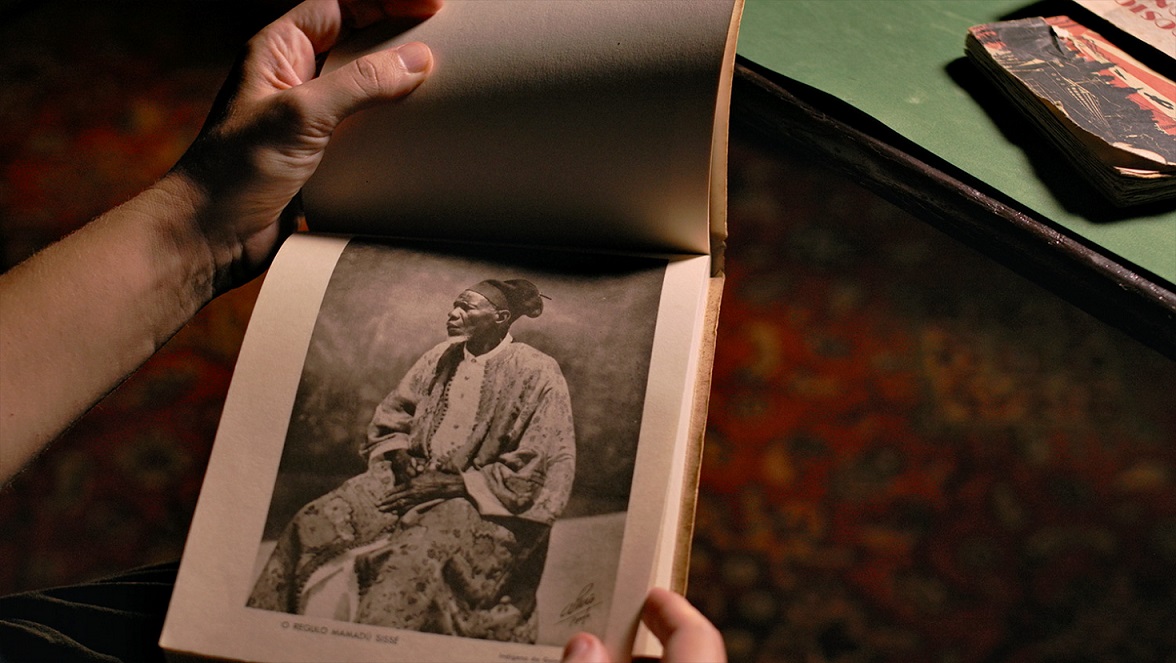

The film focuses on the ideology revealed by the 1934 Colonial exhibition, which Pessoa says is still an unacknowledged influence in public life: Portugal the caring head of a global family was the myth promoted during 48 years of Salazar’s dictadura.

The exhibition featured typical ‘villages’ from African colonies and a woman called “Rosinha” brought from what is now Guiné-Bissau was turned into a semi-naked pin-up promotional image for this human zoo.

The exhibition featured typical ‘villages’ from African colonies and a woman called “Rosinha” brought from what is now Guiné-Bissau was turned into a semi-naked pin-up promotional image for this human zoo.

What are your interests as a filmmaker?

I began looking at our colonial history, and womens’ experiences because it all seems to be reflected in today’s Portugal, 48 years of dictatorship is still very present as a trauma. I began with the experiences of women in the colonial wars, in my film “Warriors” in 2011. And the triple desire to conquer, possess and civilize these people was there in the body of the Guineense women, presented half-naked to the gaze of the public in Porto in 1934. These people brought from Africa were made to build replica native villages, unpaid, a 19th-century style human zoo, and one woman given the name of Rosinha was featured always half-naked on the covers of magazines and in publicity.

The purpose of that exhibition was to show the Portuguese how to behave, and how to look at the Other, and this lesson was so well learned during Salazar’s time that we still think in that way: that we are more caring than other colonial nations, one big happy family not like the brutality of the Belgian Congo.

But that’s a lie, because the political police, the PIDE worked together with the army in Africa, not as we are told, only in Portugal, and both were very brutal. The official narrative is that the revolution of 25 April 1974 was just instigated by the army on behalf of the people, ignoring the role of the liberation movements in Africa.

But that’s a lie, because the political police, the PIDE worked together with the army in Africa, not as we are told, only in Portugal, and both were very brutal. The official narrative is that the revolution of 25 April 1974 was just instigated by the army on behalf of the people, ignoring the role of the liberation movements in Africa.

We still have the Praça do Imperio in Belem, where they installed this year in 2023 a collection of stone shields in the pavement showing Angola, Guiné, Goa, Mozambique, São Tome and Principe, and Timor, alongside the provinces of Portugal as if they were all part of one country. It was supposed to commemorate the Imperial Exhibition of 1940 that took place there, but it isn’t even authentic, the design is actually from the 1960s. People say that we can’t erase history – but no, this is history being created in 2023.

Has the BLM movement and the removal of statues of slave traders in the UK had an effect in Portugal?

There has been a project for a long time to make a monument to enslaved people in Lisbon where the slave market existed in the 16th Century – and even though it is just a small memorial, not a museum, it has been postponed many times and work has still not started.

Many people in Britain are saying that we haven’t got over our imperial nostalgia, is that true of Portugal?

The people now in their 60s or 70s who were born in Africa will still say that they are Angolans or Mozambicans, not Portuguese.

A lot of the people who were sent there from Portugal came from poor families here, achieved a good lifestyle there and then came back to poverty again here.

And some of them had parents and grandparents who were born in Africa so it’s difficult to say that they are not African.

Like the “Pieds noirs: who were born in Algeria?

Exactly. A lot of these people consider themselves Africans but better than the indigenous people, and since the extreme party Chega appeared some of them have become more outspoken, saying things like ‘we built the roads and developed the country and when we left it turned into a chaos’. To them they were born in a place that was then part of Portugal.

You mentioned that the Guineense people were given more prominence at the exhibition. Why was that?

Because the people from Portuguese Guiné were seen as the least like the Portuguese, and therefore could be presented as more ‘exotic’.

There were black students from a school in Lisbon in the film and also a lot in the audience. How is colonial history taught in schools here?

There were black students from a school in Lisbon in the film and also a lot in the audience. How is colonial history taught in schools here?

Even in schools where most of the students come from Luso-African families they have to find out about Amilcar Cabral and the liberation movements by themselves.

Even the left-wing parties have not been very concerned with these questions, and have you ever noticed the Portuguese parliament? The debate about positive discrimination is only in terms of socio-economic conditions. The official Census questionnaire does not include ethnic origins either.

Will you be showing the film in schools or universities?

I have shown my previous films, so I hope so, the teachers are often quite keen, but the way the curriculum is designed it doesn’t provide opportunities to show and debate films on any topic.

Slavery was not discussed in the film. Why not?

It belongs to a different period, and slavery and colonialism are different stories although they connect.

The voice-over from the 1934 exhibition includes a part saying that lesser-educated Portuguese people need to understand that the colonies are important sources of two things: wealth and labour. So, they admitted the exploitation?

The voice-over from the 1934 exhibition includes a part saying that lesser-educated Portuguese people need to understand that the colonies are important sources of two things: wealth and labour. So, they admitted the exploitation?

It was like slavery, but it wasn’t called that.

In São Tome, the workers were paid but they could only spend their money in the government shop where prices were high. And in Angola there were certain jobs that you could only apply for if you were white and Christian and ‘civilized’.

There was a large procession of people in traditional costumes from the Minho region of Portugal performing traditional dances. Why were they brought to the exhibition?

The regime always held up this image as the ideal of pure Portuguese nationality and the Minhota woman was contrasted with the half-naked African woman who could legitimately be the subject of a prurient gaze.

Their preferred image of Portugal was a rural one, not concerned with industry and progress, and the mission of Portugal was to establish a similar farming economy in its overseas ‘provinces’.

You showed an actor playing ‘Rosinha’ being dressed in the same traditional Portuguese costume. Why? I found it rather disturbing, as if when she were dressed like a Minhota she would become acceptable.

You showed an actor playing ‘Rosinha’ being dressed in the same traditional Portuguese costume. Why? I found it rather disturbing, as if when she were dressed like a Minhota she would become acceptable.

But couldn’t she be Portuguese?

It’s quite common for reporters to ask a black person where they are from, and if they say they are Portuguese, the reporter says: “But, where are you really from?” And sometimes in shops you hear people talk to Africans with the familiar ‘tu’ form – which is only used for friends or younger people, so it’s a way of infantilizing them.

Are you working on a new project?

I am starting to prepare a TV documentary series about Portuguese women writers who were never recognized during the Salazar years.

(Photos supplied by the interviewee and authorised for publication.)

.jpg)