Charities supporting survivors of sexual violence speak out about Now Then data showing disabled women are half as likely to see their attackers charged with a crime.

Content note: discussion of rape and sexual assault

The Centre for Women’s Justice reports that 85,000 women are raped in the UK every year. Of these, two in ten report to the police.

These numbers come as no surprise to Meera Kulkarni, Chief Executive Officer at Sheffield Rape and Sexual Abuse Centre (SRASAC), as they are reflected in the experiences of people who access their services and support.

“The last time we did stats on how many counselling service clients had reported, it was around 20%. So the inverse of that is obviously that 80% of counselling clients never report to the police. Which isn’t a surprise, but I think it is a surprise to people who aren’t used to talking about these issues,” Meera tells me.

As public awareness about rape and sexual assault improves, that is not being reflected in how many victims see justice. Meera goes on:

“There is something wrong when you’ve got the number of reports, and people’s understanding of what rape or sexual assault is going up, and [they’re] feeling that they should seek justice. Whereas the justice system is actually getting worse and worse.

There are delays in investigations and trials coming to court – and then sometimes being adjourned – which mean that people can be waiting years within the system, with their lives on hold and the burden of waiting for a day in court hanging over them.

Some people choose to withdraw because of the impact of these delays on their health and wellbeing.”

Independent Sexual Violence Advisers, or ISVAs, work with survivors at organisations like SRASAC. According to Rape Crisis, “Their main role is to provide practical and emotional support if you want to report to the police, or are thinking about reporting”.

IDAS is another Yorkshire organisation that supports survivors. Sam Beckett, their lead ISVA, tells me:

“We’re making sure [survivors we support] understand what’s happening because, let’s face it, criminal justice is the most challenging journey that anybody can ever go on. I can’t think of a better way to describe it.

So we’re making sure that they’re getting updates, that they’re aware of what the police are doing, what that looks like and, when that case is going over to CPS [the Crown Prosecution Service, which decides if cases go to court], that they’re fully aware of what that means for them.”

This work is vital because, according to Carmel Offord, also of IDAS, “There’s quite a bit of research that suggests that ISVA involvement will increase the likelihood of conviction and keeps people engaged with the criminal justice process for longer”.

This work is vital because, according to Carmel Offord, also of IDAS, “There’s quite a bit of research that suggests that ISVA involvement will increase the likelihood of conviction and keeps people engaged with the criminal justice process for longer”.

Like Natalie Shaw, Strategic Lead for Violence against Women and Girls at South Yorkshire Police outlined, Sam describes how difficult it is for rape survivors to meet the standard of evidence for a case to progress to trial:

“How do you get evidence of something that usually happens behind closed doors? It’s very rare that the perpetrator does it in front of a video camera or something that you can show. You can get really clear forensics but actually, if the perpetrator says, ‘But that was consenting,’ I think that becomes a problem.”

Carmel adds that police are often reluctant to seek charges “if they are doubtful of meeting that evidential standard.

“That goes in terms of CPS too – that evidential standard can be difficult to meet. The burden on victims to provide the evidence is quite often overwhelming. And that presents barriers for particular groups of people, doesn’t it?”

This leads to an additional – and significant – problem, which the Justice Gap series is exploring: people who are marginalised by society are having an even harder time accessing justice, often on top of being more likely to be victimised in the first place.

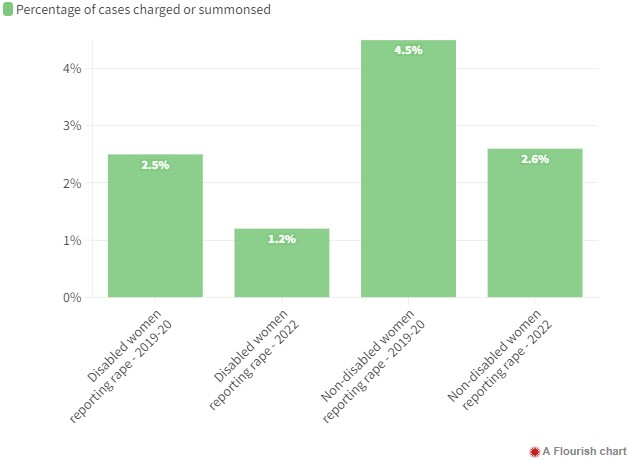

As Now Then has revealed, disabled people are twice as likely to experience sexual assault as non-disabled people, but when disabled women report rape in South Yorkshire, we are half as likely to see anybody charged with a crime as non-disabled women.

This increased targeting could be explained, in part, by how perpetrators and society at large see disabled people, according to Kulkarni:

“Sometimes a person’s perceived vulnerability is the motive for attacks. Somebody might specifically target a disabled person because they won’t be believed, or because they can’t communicate […] or they’re very isolated.”

“Sometimes a person’s perceived vulnerability is the motive for attacks. Somebody might specifically target a disabled person because they won’t be believed, or because they can’t communicate […] or they’re very isolated.”

Similarly, Offord points out that sexual predators are motivated by power and control:

“They’re seeking anybody that they can have that power and control over. They’re looking for ways that they can do things that fall just short of the law, or make it harder for the law to be applied.

So I think one of the reasons why we see such an over-representation of disabled women who have been subjected to domestic abuse or sexual violence is because perpetrators will seek out those opportunities. It’s a horrific fact that they do that.”

Percentage of people aged 16 to 59 that experienced any sexual assault (including attempts) in the 12 months to March 2018 by disability status and sex

Meera Kulkarni of SRASAC tells me:

“The stats for convictions for rapists and sexual offences are terrible in general. But understanding how the world works – in relation to individual and systemic discrimination and oppression, and how life might be more difficult for certain for different groups – that surely is common sense.

You don’t need stats to understand that if you have a disability, engaging with the world and seeking justice is going to be probably more difficult.

The police have a duty to actually understand what they’re dealing with. Because I do think, as well, it’s those intersectional oppressions that people deal with.

The police have a duty to actually understand what they’re dealing with. Because I do think, as well, it’s those intersectional oppressions that people deal with.

So if you were an Asian woman from a Pakistani background, who maybe didn’t speak English, who might also have a learning disability as well as a physical disability, how is she going to seek help? Compared to a university student who might be coming from a really wealthy background, very articulate, have lots of support in place?

It’s a completely different story.”

Carmel Offord agrees:

“You’ve got all the usual victim-blaming attitudes, but in addition to that, you’ve also got assumptions around disabled people’s sexuality, which can sometimes be [that they are] stereotyped as asexual or they’ve got a sense that, ‘Nobody would do that to you’.

There’s a sense that there isn’t those kinds of perpetrators, whereas we know statistically there are, and that disabled women face those additional barriers to being believed and accessing support.”

She also points out that in the current system, survivors have to be “compelling” witnesses who give “their best evidence”:

“And all of those barriers become very real for disabled victims in particular. It’s an arduous process for anybody, but it’s likely to impact on people differently depending on their personal circumstances. And I imagine that that makes [getting justice] less likely.”

Percentage of reported rapes leading to charge or summons in South Yorkshire

Data broken down according to whether the victim was disabled or non-disabled

Victim blaming narratives are widespread in nearly all rape cases, but can be even more powerful when a rape victim is disabled.

Referring to the phenomenon of disabled rape survivors not being believed, or having their understanding of what happened to them questioned, Offord says that, because society does not want to believe that there are people who would target disabled women, the prevalent conclusion is that “it must be the victim who’s misunderstood, got it wrong”. She thinks that view is probably “pervasive throughout society and into our institutions, as well.”

Whether disabled survivors are getting enough support through the criminal justice system is also vital to address, given the improved success in cases where ISVAs are involved. This leads Sam Beckett to question whether disabled women are being offered the advocacy and assistance they are entitled to.

“It would be really interesting to see, with women with disabilities, if they have been able to access ISVAs and what support were they offered. Because they should have been offered an ISVA at the point of going to the police. But I wonder how many people were.

It’s things like having an advocate who’s fully aware of what additional support that person needs to be a good witness, how to give that evidence in a way that makes that clear. And it’s understanding what it means to come forward and talk about that.”

It’s things like having an advocate who’s fully aware of what additional support that person needs to be a good witness, how to give that evidence in a way that makes that clear. And it’s understanding what it means to come forward and talk about that.”

“What support do they need in the very beginning to do that interview? How do they get support to get to that point, to be able to go in and do that?

Because it’s not set up for any victim. And then you bring in a disability, that makes it even more difficult. It’s just an additional barrier, isn’t it?”

But things can be done. Carmel Offord tells me that “community-based support services like IDAS, like the other fantastic sexual violence services in South Yorkshire, can really support people to understand what’s happened to them.

“If you do get any of that slight pushback, or that victim-blaming attitude, or that questioning of what happened, and you haven’t got that support, you may just feel that it is too much. And that will really take the wind out of your sails from pursuing a criminal justice investigation.

“And so I think the community-based support that teams can offer is really, really vital.”

Specialist charities like SRASAC and IDAS exist to work with survivors, whether they want to report to the police or not, and they are keen to accommodate people who may feel alienated or unsupported.

As society slowly starts to listen to survivors, the criminal justice system needs to catch up. In particular, it needs to stop replicating and magnifying the oppression we see in the rest of society.

As society slowly starts to listen to survivors, the criminal justice system needs to catch up. In particular, it needs to stop replicating and magnifying the oppression we see in the rest of society.

Ultimately, Meera Kulkarni tells me she is “cynical, but optimistic as well. You know, I do believe that change is possible.”

If you are a disabled survivor of sexual violence and want to talk to me – anonymously, if you prefer – for the Justice Gap series, email me.

*Article originally published in Now Then magazine.

(Photos: Pixabay)

Philippa Willitts*

Philippa Willitts*

.jpg)