Relationships and feelings are untidy, friends and family are those you only think you know, the libidinal is a minefield, mistakes and misinterpretations are made, regrets are buried and then – out of the blue, the unconscious or the cunning of reason – something returns, resurrected, unwanted; the truth can hurt.

Sean Sheehan

Sean Sheehan

Such aspects of existence are delicately crafted in the fiction of Te ssa Hadley and, being undeniable aspects of life’s fragility, they strike a chord with most readers.

In “Dido’s Lament” a woman, now in her thirties, encounters her ex-husband after a gap of nine years and has a glimpse of his rebuilt life.

They part and the man is left trying to forget that everything he’d put together since their separation was there to show her, and himself, that he had a life without her.

If he can stop thinking this then “at some point it could no longer possibly be true, and he’d forget he’d ever thought it might be.” The woman wonders if she will contact him again: “It really was better to be free. Or if it wasn’t better, then it was necessary”.

Put reductively, the ex-husband relies on Lacan’s big Other, the socio-symbolic order conferring coordinates and coherence, while the woman accepts the abyss of freedom and the angst it entails.

Three sisters, in “The Bonny club”, are now of retirement age and they return to the family home to attend their mother who has been taken to hospital, “waiting more probably for their mother to die, and for the end of their past”.

They recall their younger lives in the house but much time has passed, their own adult lives are beginning to fade and only a spider’s thread of memories now connects them. In a way that is desperately sad, they have become strangers to who they were as children.

They recall their younger lives in the house but much time has passed, their own adult lives are beginning to fade and only a spider’s thread of memories now connects them. In a way that is desperately sad, they have become strangers to who they were as children.

In another story, a woman with no children of her own finds herself looking after her step-daughter for a week. She emerges as a subject who is not a free agent, her selfhood is the result of forced circumstances beyond her control.

She finds she has to choose herself, not from a god-like position of knowledge but through the weight of ethics and the unanticipated presence of another woman and a child.

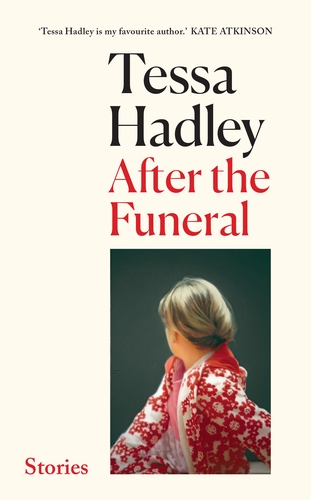

Hadley writes about feelings, not ideas, and how they change or get revealed is the stuff of her fiction. The short stories in “After the funeral”, a series of minor domestic epiphanies, texturize life’s messiness and complicate characters’ subjective positions.

There is elusiveness about the narratives and the shifts in relationship allow and invite self-reflection. In “Old friends”, a person who –not the rarest of breed– is described as one of those men who thrust his imperfect body shamelessly, even keenly, in your line of sight, with a winning, uninhibited unconsciousness, as if he’d never noticed he wasn’t a cherub any longer’.

There is elusiveness about the narratives and the shifts in relationship allow and invite self-reflection. In “Old friends”, a person who –not the rarest of breed– is described as one of those men who thrust his imperfect body shamelessly, even keenly, in your line of sight, with a winning, uninhibited unconsciousness, as if he’d never noticed he wasn’t a cherub any longer’.

Knowing yourself can be a tricky business.

“After the funeral”, by Tessa Hadley, is published by Jonathan Cape.

(Photos: Pixabay)

.jpg)