Violence was all around Walter Benjamin when he set down to write “Toward the critique of violence” in December 1920.

Sean Sheehan

The First World War had only been over for two years, the German Revolution had been ruthlessly suppressed in 1919 and nine months earlier a right-wing coup in March had been defeated by a general strike.

He mentions none of these events but they are the background to what he writes, just as the ‘Stop the boats’ campaign by the UK government and Palestinian violence can be to a contemporary understanding of what he wrote.

Early sections in “Toward the critique of violence” are difficult to warm to because of their abstract reflections on law and arguments around breaking it in terms of means and ends. Matters become more interesting when, a few pages later, Benjamin introduces a distinction between two kinds of violence: the ‘mythic’ and the ‘divine’.

He illustrates mythic violence with the Greek myth of Niobe, all of whose children were slaughtered for her affront to the gods Apollo and Artemis.

Niobe herself was not killed but came to be turned into a rock, thereby ‘marking the border between human beings and gods’. What is established is a boundary and the foundation of the retribution for transgressors is violence.

Niobe herself was not killed but came to be turned into a rock, thereby ‘marking the border between human beings and gods’. What is established is a boundary and the foundation of the retribution for transgressors is violence.

The UK government seeks to make the Channel between Britain and France an equally absolute boundary, one between two types of people – those deemed to belong and those from elsewhere who seek refuge. Legal measures, from barges and the courts to extraction overseas, are designed to enact the boundary as petrifyingly as Niobe’s transformation into stone.

Only divine violence will effectively oppose the legal order’s violence and Benjamin describes the distinction in language that is metaphorical, messianic and theological.

If mythical violence is law-positing, divine violence is law-annihilating; if the former establishes boundaries, the latter boundlessly annihilates them; if mythical violence brings at once guilt and retribution, divine power only expiates.

If mythic violence is what Israel is daily implementing in the West Bank, divine violence is one way of marking the resistance by Palestinians to settler colonization in their land. There is no criterion, like the “Thou shalt not kill” commandment, for a judgement. Of the commandment, Benjamin says it exists “not as a standard of judgement but as a guideline of action for the agent or community that has to confront it in solitude and, in terrible cases, take on the responsibility of disregarding it.”

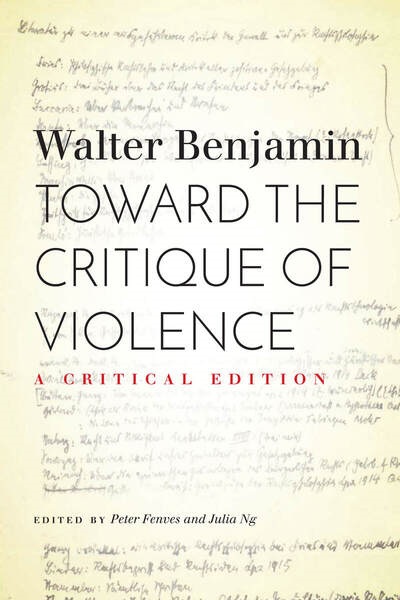

A new edition of Benjamin’s allusive essay helps elucidate what is often enigmatic and esoteric about a text whose author is working towards a more Marxist perspective.

It is fully annotated and includes a large and helpful selection of notes and fragments by Benjamin that are closely related to what he was formulating.

The edition also includes selected passages from books and articles that Benjamin refers to in his essay

“Toward the critique of violence: a critical edition”, edited by Peter Fenves and Julia Ng, is published by Stanford University Press.

.jpg)