Nudism was never part of her lifestyle but Virginia Woolf liked to remind friends she was inviting to her house to “bring no clothes”.

Sean Sheehan

What she meant by ‘clothes’ was traditional fashion which in the 1920s dictated how upper class women and men should dress, a codification which lingers on today with the prevalent assumption that posh dining out requires attention to dress.

Charles Porter takes six members of the Bloomsbury group, to which Virginia Woolf belonged, and shows how each of them dealt with this codification.

Woolf could be described as non-binary or trans and Porter is right to avoid the tiptoeing around it as so many accounts of her life and work have done.

In one of her novels, “Orlando” (1928), the main character transitions from male to female, at which point the author writes how clothes ‘change our view of the world and the world’s view of us’ and how gender binary is a social construct mediated by the clothes we wear:

In every human being a vacillation from one sex to / another takes place, and often it is only / the clothes that keep the male or female likeness, / while underneath the sex is the very / opposite of what it is above.

In every human being a vacillation from one sex to / another takes place, and often it is only / the clothes that keep the male or female likeness, / while underneath the sex is the very / opposite of what it is above.

The economist John Maynard Keynes was also in the Bloomsbury group, decidedly gay as a young man and later bisexual, but his way of dressing– invariably attired in a suit, shirt and tie – reflected the deep conservatism of his class; he never sought escape from sartorial constraints.

One of his many lovers was the painter Duncan Grant who, unlike Woolf, did like to be naked (just as he liked to paint male nudes) and Keynes took photographs of him undressed when they holidayed in Greece.

When he did dress, as Porter shows through a series of photographs, he did so with an insouciant disregard for convention that may help explain why Woolf’s sister, Vanessa, loved him enough for them to live together for more than forty years.

Sex within the Bloomsbury group, complex and fascinating, is a theme of this well researched and hugely readable book.

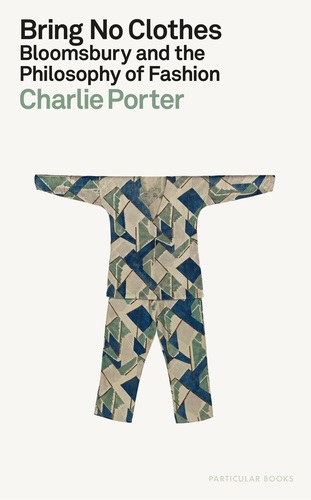

Charlie Porter is a fashion writer and the strength of “Bring no clothes” lies with the wealth of photographs showing how the Bloomsbury group dressed and undressed and his writing at his best flows from his reading of them.

Porter is not blind to the class structure of the society which positioned the Bloomsbury group as a privileged upper middle-class group who did not have to worry about poor wages.

He looks, for example, at how their servants dressed at work in the kitchens and around the houses of their employers.

He admires the servants’ loose, patterned and sometimes pocketed garments that allowed ease of movement – noting how manufactured versions are sold today at high prices but that those making them do so for minimum wages and those delivering them to online customers are probably on zero hour contracts.

“Bring no clothes”, by Charlie Porter, is published by Penguin.

(Photos supplied by the publisher)

.jpg)