It is common to think of taxonomy, the branch of science concerned with classification, in terms of hierarchy: divisions between Kingdom, Phylum, Class, Order, Family, Genus, Species (made easier to remember with the mnemonic Kieran, Please come over for gay sex) are seen to define the natural order in much the same way as ranks in an army structure of command.

Sean Sheehan

Sean Sheehan

It reinforces a way of thinking about people as being determined by their place within a ‘natural’ hierarchy. Trees don’t do this.

The nomenclature brought to mind with Kieran’s invitation is associated with Carl Linnaeus and was developed before genetic analysis became possible. Phylogenetic classification, which is based on genetics, avoids the nested hierarchy of Linnaean classification and does not assign ranks. Incidentally, the Bolsheviks in 1917 abolished army ranks, along with salutes, insignia and decorations but, like many of their revolutionary cultural reforms, the status quo was restored under Stalin.

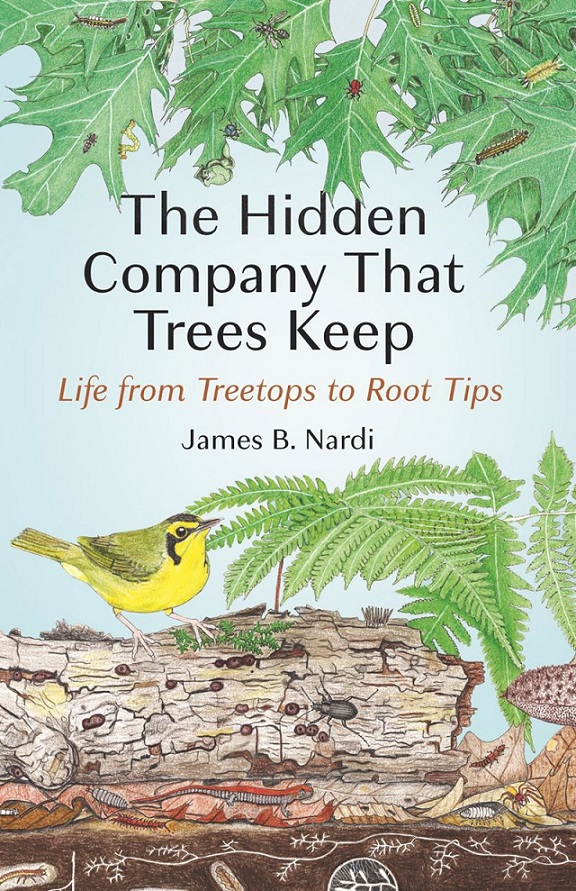

For the forms of organization that trees have evolved, the book to turn to is “The hidden company that trees keep”.

Notions of hierarchy give way to the idea of a complex web of partnerships, involving birds, mammals, insects and countless smaller creatures, and the inaugural exchange when green plants developed the ability to utilize the energy of light, via molecules of chlorophyll, to produce sugars and oxygen from the raw materials of carbon dioxide.

Notions of hierarchy give way to the idea of a complex web of partnerships, involving birds, mammals, insects and countless smaller creatures, and the inaugural exchange when green plants developed the ability to utilize the energy of light, via molecules of chlorophyll, to produce sugars and oxygen from the raw materials of carbon dioxide.

While this is learnt at school, what escapes attention are the tiny microbes– including fungi, protozoa and bacteria – that interact with a tree’s tissues and cells.

The scale of a tree’s company is astonishing: many of the microbes are smaller than the period at the end of this sentence while at least 1,000 different insect species depend on oak trees for their livelihood. The maidenhair tree (Ginkgo) prefers life without them and produces chemicals that repel but do not kill insects.

“The hidden company that trees keep” is wonderfully accessible because, as well as being full of fascinating information and written by a research scientist, it is not presented in the style of a botany textbook.

Most pages have precise black-and-white drawings relating to the topic under discussion, engaging with and encouraging the reader to linger and absorb what is being said at a leisurely pace.

One chapter is devoted to the miniscule animals that tap – literally in the case of woodpeckers – into a tree’s circulatory system whereby sap flows between treetops and root tips. In the roots, sap picks up minerals and water; in the leaves it picks up sugars produced by photosynthesis; and after the tree has taken its share of nutrients from the sap, the leftovers are taken up by the birds, mammals and insects.

Other chapters reveal the myriad ways by which trees share life with other creatures without the need for hierarchy and ranks of authority.

Other chapters reveal the myriad ways by which trees share life with other creatures without the need for hierarchy and ranks of authority.

“The hidden company that trees keep: Life from treetops to root tips”, by James B. Nardi, is published by Princeton University Press.

(Photos: Pixabay)

.jpg)