Epics and mythical stories were good at visualizing beasts that only a hero or a god could defeat. Such creatures tend not to appear in modern-day novels but dementia could be described as a monster that hasn’t gone away, one that is continuing to grow more fearsome.

Sean Sheehan

Sean Sheehan

Old age is the battle that each of us has to fight, ‘without hope that bards will sing songs about you’, and – discounting fond illusions that some divine presence will save us – the title of one of Munch final’s self- portraits is quoted as best summing up the narrow territory where the final combat is to be fought: “between the clock and the bed”.

In the novel’s European geography of aging, “Time shelter”, Paris, Berlin and Amsterdam are for youth; Vienna and Brussels for maturity; Rome, Barcelona and Madrid for postponing the decline into decrepitude; Zurich alone is deemed a good city in which to grow old (London is presumably off the scale and has no rating).

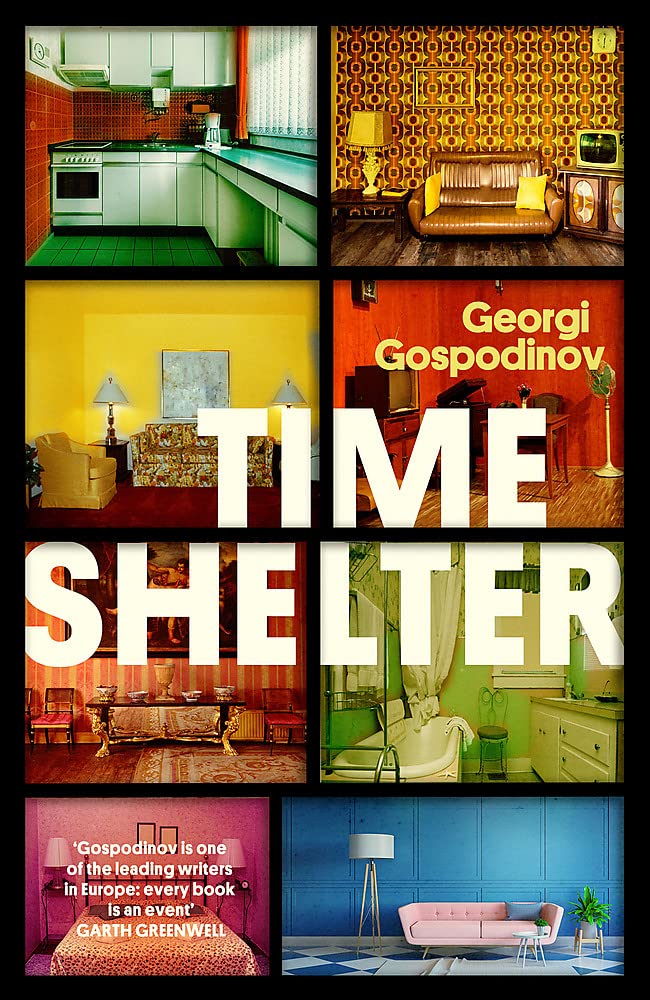

Zurich also has the distinction of being seemingly ahistorical, always neutral, and it is here that Gaustine, the central character in “Time shelter”, establishes a sanatorium/clinic that recreates a period of the past.

It offers a promising treatment for Alzheimer sufferers by allowing them to inhabit their chosen decade of the past, complete with daily newspapers of the era and period details of décor.

The first sanatorium begins with the 1960s but the idea proves successful and expands to other time slots and clinics elsewhere. Healthy people turn to them as therapy, a ‘time shelter’ to escape troubles of the present.

The first sanatorium begins with the 1960s but the idea proves successful and expands to other time slots and clinics elsewhere. Healthy people turn to them as therapy, a ‘time shelter’ to escape troubles of the present.

This novel, about the centrality of memory to our sense of being, asks a question: “If we are not in someone else’s memory, do we even exist at all?”

It is true that deceased loved ones continue to exist, in a non-corporeal but deeply felt way, for those who remember them. But perhaps we also imagine parts of our memories as a way of telling stories to ourselves, to tell us who we are, fictions to persuade us we are that same person who existed in the past.

We need a plot – like those created in movies – but, as a character in the novel admits, there is no plot: “And therein lies the deep anti-cinematographic-ness of life. Nothing but leaving home, coming back.”

The unnamed narrator, Gaustine’s assistant, asks if it is wise to resurrect the past and his question becomes a pressing one when politics move in on the idea.

The unnamed narrator, Gaustine’s assistant, asks if it is wise to resurrect the past and his question becomes a pressing one when politics move in on the idea.

Political parties gain traction by offering to recreate different eras of their nation’s history and referendums are held on what period of will appeal most to voters.

“Time shelter” may be a work of fantasy but there is nothing fictional about some people’s willingness to believe in false versions of their own and their country’s past.

“Time shelter”, by Georgi Gospodinov, is published by W&N (Weidenfeld & Nicolson).

(Photo: Pixabay)

.jpg)