There was a documentary released on BBC TV on Picasso, in October 2023. It focussed primarily on Picasso and his relationships with women. What came out was the failure of the various commentators and interviewees to reconcile the two (alleged) sides to Picasso, his ‘great’ art, and his controlling behaviour towards women―conspicuously violent and sexually abusive.

Nigel Pocock

Some interviewees preferred the irrational strategy of separating this total egocentricity from his art, creating a psychological and neurological dichotomy. This is completely rediculous―Picasso was one whole, and both his art and treatment of women flow from the same source, his huge ego.

Picasso, is, of course, far from being the only ‘great’ artist who has behaved in this way (think, for example, D-G. Rossetti and Lizzie Siddall, and many others). But why? Philippa Perry (psychotherapist wife of Grayson) suggested that the need to control is part of this, although she rather backed off from trying to explain how the Great Man’s art and violence could be part of an integrated whole. She was not the only one, such is the reverence for the Great Man.

Yet the explanation is not complicated. Steve Taylor, recently discussed in the pages of The Prisma, provides part of the explanation―egocentricity and consequent disconnection and lack of empathy. It is only complicated to those who fail to understand that Picasso’s art is as much a part of his huge ego, as his treatment of women.

Taylor traces this back to the ancient tradition of the ‘fall’―evident in many ancient cultures―together with an absence of weapons in the archaeological layers of a prehistoric gatherer era, before a settled, Neolithic (farming) world.

A gatherer society was altogether different from the incipient capitalism and individualism which followed, with its ‘me (or my culture) first’ attitude―with its dynamic of attitude-action feedback and reinforcement.

A gatherer society was altogether different from the incipient capitalism and individualism which followed, with its ‘me (or my culture) first’ attitude―with its dynamic of attitude-action feedback and reinforcement.

Hence, Picasso. But Taylor is completely wrong on the ‘open sex’ that he alleges. Looking at the Biblical version of the ‘fall’ (Genesis 3) John Walton comes to a completely different conclusion. In an examination of the various Hebrew and other ancient Near Eastern words, Walton finds that far from encouraging an open sexuality―as Taylor and Picasso would have it, and used to exploit women―the reverse is the case. The alleged ‘rib’ from which Eve (‘mother of all living’, and likely an archetype) is made from ‘the adam’ (‘the man’, another archetype) and is actually an architectural term (and is used in this way in other parts of the Old Testament, especially as regards the building of the temple). It is not a biological term.

The ‘deep sleep’ in which the man (‘the adam’) is in when his ‘side’ is removed, is very likely a trance or vision-like state, in which he experiences the ‘creation’ of Eve, not a surgical procedure. Again, the word is used in this way elsewhere in the Old Testament, for example in the trance-sleep of the prophet Daniel.

The conclusion that Walton draws is that of a literally-envisioned ‘soul-mate’ experienced in a dream, not the transient sexuality of a purely biological union, but a vision of a relationship that is permanent, mutually loving and committed, a vision of a deeper level of reality.

The conclusion that Walton draws is that of a literally-envisioned ‘soul-mate’ experienced in a dream, not the transient sexuality of a purely biological union, but a vision of a relationship that is permanent, mutually loving and committed, a vision of a deeper level of reality.

This is the exact opposite of the totally egocentric, abusive, and controlling Picasso. Picasso wanted to be God, believed he was God, and wanted his women to worship him. His cultured admirers, too. Some interviewees tried to excuse and exonerate Picasso (as Philippa Perry does) in terms of the old chestnut of ‘a product of his time’. This might be partly true. But only partly. Picasso had free-will. One could say the same about the slavers in the Caribbean.

They abused people left, right, and centre. Products of their time? Yes―but there were always alternative definitions of reality available―if only they wish to choose them. Picasso chose to align himself with a certain artistic clique, with its mores, values, attitudes and reinforcing actions. Atrocities become easier with practice, and, as his egocentricity and increasingly conditioned behaviours reinforced this. With this would have been legitimating excuses, increased dissociation and lack of empathy.

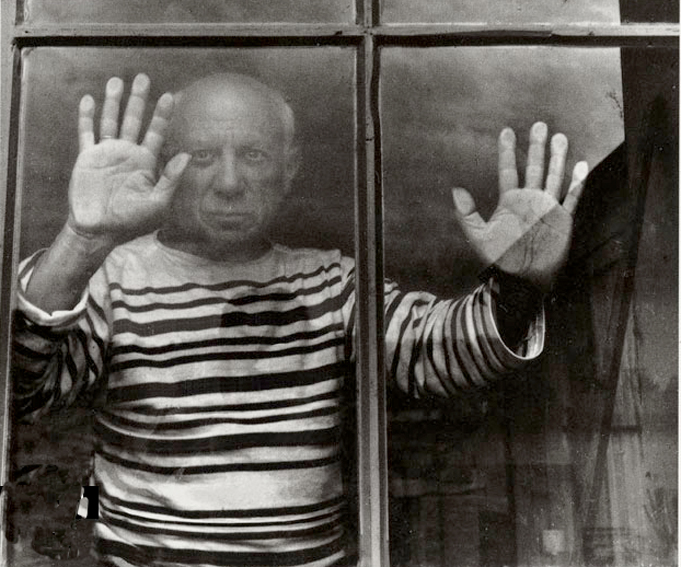

There were huge fears in Picasso, especially of death. He chain-smoked (hardly a photo shows him without his nicotine ‘fix’). Today we know that tobacco contains a natural antidepressant (utilised by the slavers to ‘pacify’ their prisoners on board ship).

There were huge fears in Picasso, especially of death. He chain-smoked (hardly a photo shows him without his nicotine ‘fix’). Today we know that tobacco contains a natural antidepressant (utilised by the slavers to ‘pacify’ their prisoners on board ship).

Perhaps Picasso was similarly depressed, but in very different circumstances? Much of his behaviour suggests that he probably was depressed. How much of his goes back to his parenting? The Roman Catholic ethos of his native Spain? The fascism of Franco, and cultural authoritarianism? This was not explored in the film, but should have been. Why was Picasso obsessed with the violence of the bull-ring? Debra Niehof (Johns Hopkins University) relates how male violence is associated with the need to win, and how winning is the key ingredient in raised testosterone.

Picasso fought to the very end of his 91 years―to be the top innovator, as well as the top predator. We will leave him there, with an art and abuse that come the same source: his undivided ego.

(Photos: Pixabay)

.jpg)