Hegel remarked about the Peloponnesian War that its importance is that it allowed Thucydides to write about it and the same could be said about another armed conflict from the ancient Greek world: the struggle between an alliance of Greek states and the city of Troy, in what is now the west coast of Turkey.

Sean Sheehan

Sean Sheehan

There probably was some such conflict around the 13-12th century BCE but, as told by Homer in the “Iliad”, it becomes more myth than history.

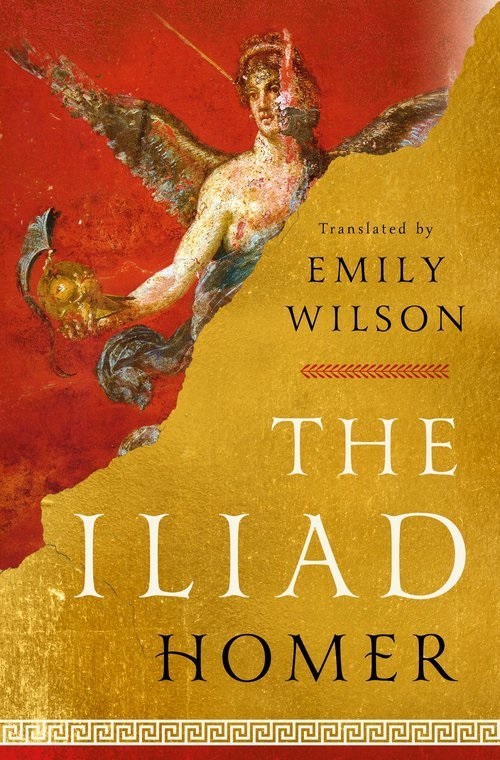

The “Iliad”, originally an oral tale, was first written down around the late 8th or early 7th century BCE and, having survived for over two and a half thousand years, it has been translated into many languages. The latest translation into English is by Emily Wilson and, like her earlier translation of Homer’s “Odyssey”, uses a regular meter and closely follows the lines of the original Greek.

An English critic said somewhere that he was not going to watch a new film version of Jane Austen’s “Emma” because everyone was praising it for being ‘so contemporary’.

When he read something about the past, he explained, he didn’t want it turned into a version of the present world; what matters is imagining what it was like to inhabit that past.

When he read something about the past, he explained, he didn’t want it turned into a version of the present world; what matters is imagining what it was like to inhabit that past.

Wilson’s translation superbly communicates the alien nature of the ancient Greek world, especially in the way the Olympian gods resemble the Old Testament god (Jehovah).

They are petty, disruptive and inclined to incite mortals to kill each other, as if the Greeks needed gods like these to account for their own violence.

While knowing they are the playthings of gods, Greeks and Trojans act as if they are free and responsible for their actions. They ruefully accept their frailty – “The generations / of men are like the growth and fall of leaves. / The wind shakes some to earth”, says a Trojan to a Greek – and Andromache tells her husband, Hector:

I hope I will be dead, / and lying underneath a pile of earth, / so that I do not have to hear your screams / or watch when they are dragging you away.

Hector then cuddles their baby and returns to the battlefield while she returns to some housework but ‘kept twisting and turning to look back at him’.

The “Iliad” is soaked in tenderness and concepts of honour and shame which rarely find expression in modern fiction.

Men are continually killing one another but each person’s death is their own: “He clattered down / his armour rang around him”; “his body was undone. / His spirit left him”; “Death wrapped around him”; “He bit the cold bronze, falling in the dust.”

The two sides slaughter each other, the next day “rosy-fingered Dawn appeared new born” and a Trojan, Gorgythion, whose mother was “as beautiful / as any goddess’, is hit by an arrow and ‘slumped his head sideways like a garden poppy, / weighted with seed and springtime showers of rain”.

Read the “Iliad” and weep.

The “Iliad”, translated by Emily Wilson, is published by Norton.

(Photos: Pixabay)

.jpg)