Photography in conflict zones is crucial as it portrays the events taking place there and allows the world to understand the situation. “The main reason that we are in the field is to report as much as possible the truth and reality that we are witnessing.”

Interview: Rola Zamzameh*

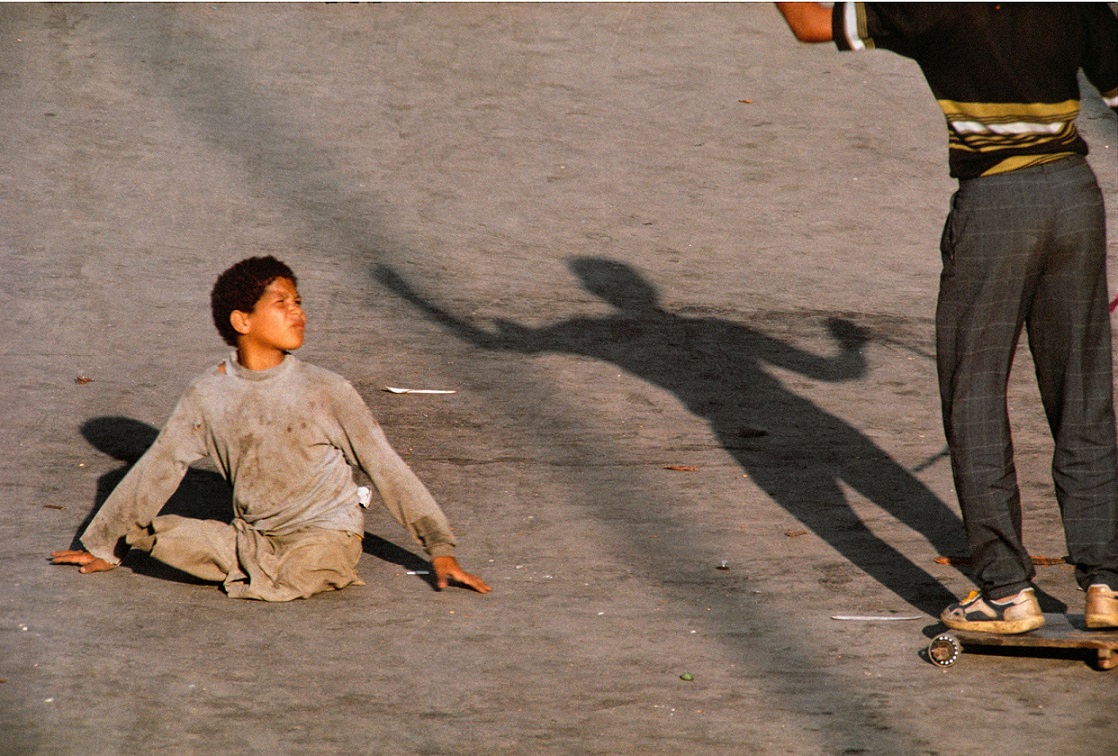

Photography: Reza

In the second part of our interview with esteemed photographer Reza Deghati (known by his artistic name Reza), we delve into the delicate interplay between respect, authenticity, and the art of storytelling in conflict-ridden regions.

With an unwavering commitment to preserving the dignity of his subjects, Reza shares his principles guiding the art of photography amidst humanitarian crises.

His profound insights shed light on the transformative power of imagery in fostering empathy and understanding.

A conversation with The Prisma over several hours unravels the nuances of his photographic journey, where beauty is intertwined with tragedy and where art stands as a beacon of hope amidst the shadows of adversity.

Your photographs often capture raw emotions and shared moments in war-torn regions. How do you manage to find the balance between respecting the subjects’ dignity and telling their stories authentically?

The main reason that we are in the field is to report as much as possible the truth and reality that we are witnessing. In this case, obviously, we are in constant contact with the population, most of the time, the population that is suffering from war, conflict, or being refugees or during natural disasters. So it’s obvious that one of the most important, and probably the first, pillars of our work will be to keep the dignity of the people that we are photographing because we want our stories of photographs to become their voice, telling the story through themselves. Thus, keeping their dignity is the most important issue.

I have a principle about my work that I should document everything that is happening around me when I am in the field. This is my historical mission because I’m there, so I have to document it so people can see what it is. But between documenting and then taking photographs, we will tell the story more through art, more through the frame which is mainly the artist’s frame. It’s a lot of work to do, preparation, and concentration in the field.

I have a principle about my work that I should document everything that is happening around me when I am in the field. This is my historical mission because I’m there, so I have to document it so people can see what it is. But between documenting and then taking photographs, we will tell the story more through art, more through the frame which is mainly the artist’s frame. It’s a lot of work to do, preparation, and concentration in the field.

What circumstances in your surroundings could prompt you to cease taking photographs at that very instant?

The only reasons why I do not take photographs are two: one if my photograph will harm the dignity of the person, whatever happens, and whoever he is, and second, which is more important, if the people are in front of me at this particular moment, they need more of my physical help. They need my helping hands to help them than just holding a camera and taking pictures. There have been many times that I have not taken pictures because people needed my hand and presence to help them.

Could you elaborate on the concept of photography as a tool for raising awareness about conflict-related issues and inspiring change? How do you see your work contributing to this goal?

What photography is achieving today, in all aspects, is the creation of relations between humanity, cultures, communities, and individuals. Therefore, it is crucial to utilize photography in conflict zones to illustrate the events occurring there, enabling people worldwide to comprehend the situation. If not for images, the number of casualties and killings by the military would be significantly higher in the present day. Thanks to social media, the impact of casualties and killings has diminished compared to the past, after the advent of photography and visual social media.

What photography is achieving today, in all aspects, is the creation of relations between humanity, cultures, communities, and individuals. Therefore, it is crucial to utilize photography in conflict zones to illustrate the events occurring there, enabling people worldwide to comprehend the situation. If not for images, the number of casualties and killings by the military would be significantly higher in the present day. Thanks to social media, the impact of casualties and killings has diminished compared to the past, after the advent of photography and visual social media.

In your photography, you often capture the beauty within tragedy. Can you discuss the significance of finding hope and positivity in the midst of adversity, and how you translate this into your images?

The main narrative is that humans are drawn to beauty. Beauty stands as a fundamental pillar of our philosophy, thoughts, and actions. Therefore, to draw attention to tragedy, I utilize beauty. Even in the eyes of those who have suffered, I capture the beauty of humanity, as it invokes a sense of protection and love.

Presenting culture through beauty attracts people’s interest and encourages them to delve deeper. Similarly, showcasing the beauty of a nation fosters a sense of protection and unity among its people.

Thus, my primary focus in all my works is to display beauty, as it serves as a gateway to uncovering what lies beyond and understanding the deeper aspects of the portrayed subjects.

Thus, my primary focus in all my works is to display beauty, as it serves as a gateway to uncovering what lies beyond and understanding the deeper aspects of the portrayed subjects.

“Memories of Exile” delves into the personal stories of refugees, making their experiences tangible for viewers. How do you hope your work impacts the public’s perception of refugees and the challenges they face?

Undoubtedly, a deeper understanding of a subject arises when it becomes personal. Personal storytelling enables people to gain a more comprehensive insight into a narrative. This is one of the primary reasons that my work fosters a connection between the viewer and the subjects in the photographs. By facilitating this face-to-face interaction, individuals draw closer to each other, and upon viewing the photographs, they gain deeper insights into the depicted stories. This approach holds true not only for refugee-related works but for all forms of my work, as it encourages this personal connection, prompting viewers to engage more deeply by looking directly into the eyes of the subjects.

Your images transcend language barriers, enabling people from diverse backgrounds to connect emotionally. How do you believe photography can contribute to breaking down cultural misunderstandings and fostering empathy?

I believe that at a global level, our civilization has entered an era where we require a unique and universal language that everyone can comprehend, and that language is now photography. Similar to how hieroglyphs were among the earliest forms of writing in ancient Egypt, serving as a pictorial alphabet, our civilization currently necessitates a new form of language, which is the language of images and photography. This necessity is underscored by the invention of emojis, which can be seen as the modern hieroglyphs of our time.

I believe that at a global level, our civilization has entered an era where we require a unique and universal language that everyone can comprehend, and that language is now photography. Similar to how hieroglyphs were among the earliest forms of writing in ancient Egypt, serving as a pictorial alphabet, our civilization currently necessitates a new form of language, which is the language of images and photography. This necessity is underscored by the invention of emojis, which can be seen as the modern hieroglyphs of our time.

From your perspective as a photographer who has witnessed both the aftermath of conflict and the strength of humanity, what role do you see art playing in the healing and reconciliation processes of war-affected communities?

War, conflicts, refugees, and natural disasters have undeniably inflicted profound trauma on all those involved, ranging from politicians and soldiers to individuals on the ground, neighbours, family members, and even journalists. This trauma can leave lasting effects, prompting extensive studies across various domains to determine the most effective methods of healing.

I believe that art therapy stands out as one of the most effective approaches. When excluding conventional medical treatments, engaging in art therapy, particularly at an advanced level, proves to be a powerful tool for healing trauma, especially among children but also for adults. Art, including paintings and various forms of creative expression, enables individuals to navigate the path of healing. Consequently, photography has emerged as a significant and pivotal component of art therapy.

I believe that art therapy stands out as one of the most effective approaches. When excluding conventional medical treatments, engaging in art therapy, particularly at an advanced level, proves to be a powerful tool for healing trauma, especially among children but also for adults. Art, including paintings and various forms of creative expression, enables individuals to navigate the path of healing. Consequently, photography has emerged as a significant and pivotal component of art therapy.

Throughout your career, you’ve documented the journeys of individuals forced to leave their homes. How has your own journey as a photographer influenced your views on the concept of home and the human longing for a place of safety and belonging?

Being a photographer and a traveller entails a perpetual life on the road. However, like many others, I too require a place to call home, a centre where my family, my wife, and children reside. For me, Paris is home, where my family is. Despite this, the reality is that I spend more than nine months of the year traveling, accumulating over 43 years of being away from home for extended periods. This lifestyle has fostered a unique perspective on family and the concept of home, challenging the balance between familial bonds and nomadic pursuits.

Nevertheless, my wife, who is a writer, and our strong emotional connection aid in navigating this challenging lifestyle. Similarly, my children contribute to this dynamic, making it manageable. While being a photographer poses its own difficulties, the presence of loved ones plays a pivotal role. I consider myself fortunate to be surrounded by individuals who share passion and love.

Nevertheless, my wife, who is a writer, and our strong emotional connection aid in navigating this challenging lifestyle. Similarly, my children contribute to this dynamic, making it manageable. While being a photographer poses its own difficulties, the presence of loved ones plays a pivotal role. I consider myself fortunate to be surrounded by individuals who share passion and love.

*Rola Zamzameh: Senior journalist of EU Commission and Parliament.

(Photos provided by the interviewee and authorised for publication)

.jpg)