The story of the film “Le Mali 70” begins in a bar in Berlin and leads to a trip taking a 14-piece band to Mali. They meet some of the famous Malian musicians who absorbed a Cuban influence and were left out of the mainstream history of World Music. Trust, collective consciousness, colonial history and cultural differences are key issues.

Graham Douglas

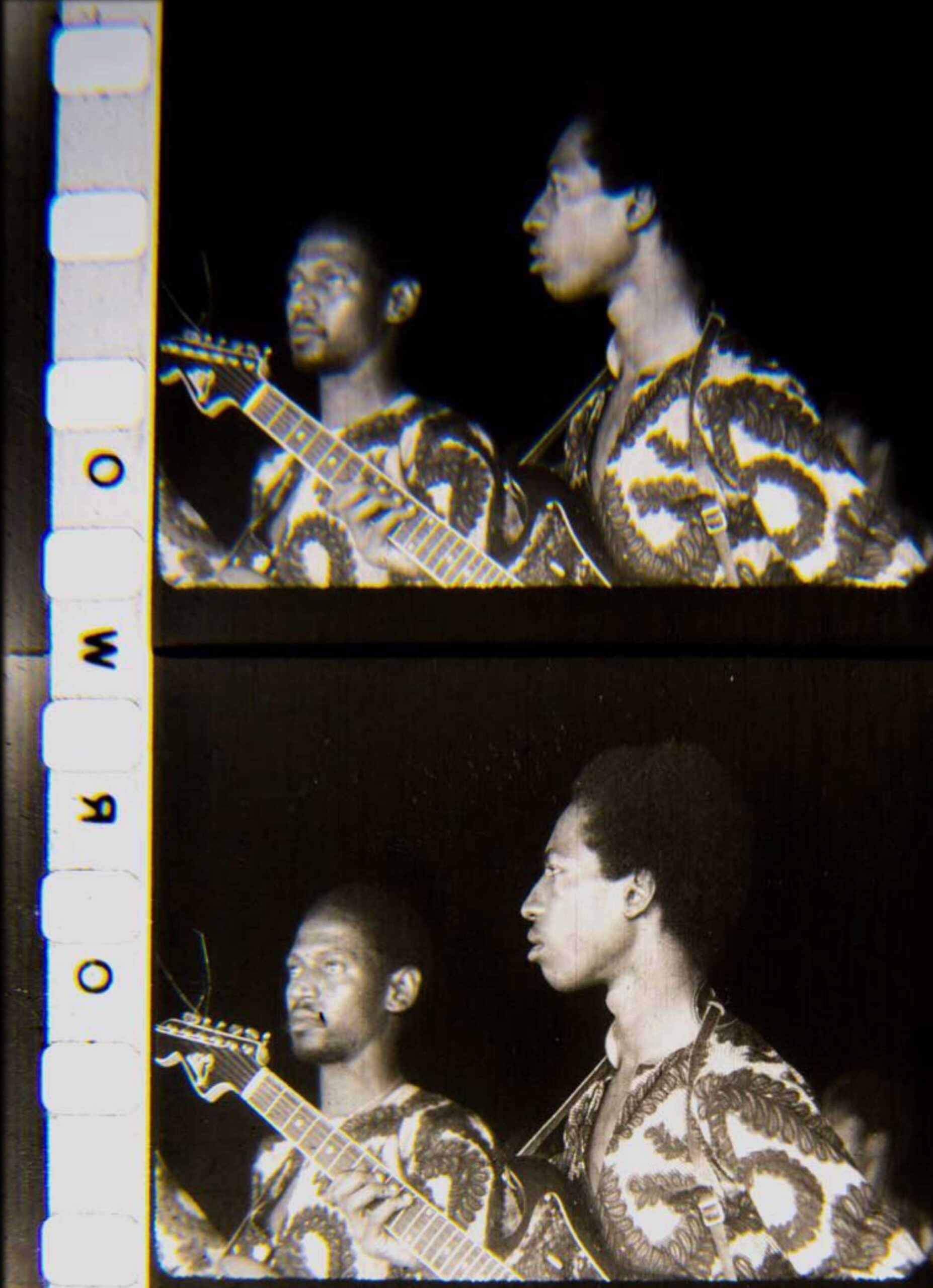

For lovers of World Music, Mali is synonymous with Ali Farka Touré and his tours with Ry Cooder. Malian traditional ‘desert blues’ guitar style is based on picking not strumming to make chords. What is much less known is the more modern style of larger Cuban-influenced jazz bands including brass sections using trumpet, saxophone and trombone. In 2010 Nick Gold, who always understood the musical chemistry between the Malian and Cuban groups finally succeeded – despite personality clashes and previous logistical problems. During 4 days in Madrid the album AfroCubism happened and was nominated for a Grammy.

Eliades Ochoa went on to record the album Cubafrica with the late great Cameroonian sax player Manu Dibango, while the late Buena Vista member Cachaito Lopez played double bass on Kasse Mady Diabate’s album Kassi Kasse in 2003.

Maybe they just missed the peak of the wave and World Music moved on, but “Le Mali 70”, available interactively online is possibly the great film that Wim Wenders might have made after “Buena Vista Social Club” if things had gone differently.

Maybe they just missed the peak of the wave and World Music moved on, but “Le Mali 70”, available interactively online is possibly the great film that Wim Wenders might have made after “Buena Vista Social Club” if things had gone differently.

Markus C M Schmidt is a German film director and editor based in Berlin, where he came to know the Omniversal Earkestra which led to travelling with them – and all their instruments including a tuba – to Mali, and making a documentary film about the trip and the musicians who created this revolution in Malian music in the 1970s.

Their programme is chosen by a different member of the band each week, but one song has become very popular: their version of the great Fela Kuti’s Colonial mentality.

The years of trust that Markus has built up with the musicians and his easy relationship with ordinary people in Mali has produced a riveting road movie that is also a historical document and a tribute to the crossover of African and Latino music.

I spent some time with Markus for The Prisma after “Le Mali 70” was shown in Lisbon last year.

Malian music is known for its blues, not brass. Did these bands come from a different area from Ali Farka Touré, or was it a Cuban influence?

Ali Farka Touré is later, but in my research, I found that it comes from the period of independence, because Malians who were in the French colonial army learned to play the instruments that military bands used. After independence, the first president Modibo Keita wanted a socialist country. He understood that music was important at that time when few people even had radios, and Cuban and Mexican Salsa was very influential worldwide at the time. Photographers were paid to take pictures at parties in Bamako, and the Party-Folks were sometimes posing holding records. In one of these photos, they are posing with an album from “Pacheco y Sus Charanga”, a Mexican salsa band. I found that photo during my extensive archive research on old photos by Malick Sidibé. Pacheco was the Railband’s drummer and named himself after that album that was hip at the time.

This is at the heart of why they decided to play similar music and incorporate a brass section. It became the music of the revolution, so it was suppressed after the military coup in 1969. Sori Bamba’s band Kanaga de Mopti had a very good brass section.

He had seen Louis Armstrong in the ‘50s and decided to learn to play the trumpet. But all his instruments were destroyed by the military after the coup in 1969. Salif Keita’s band Les Ambassadeurs in Bamako was the only band that still played, although they did not use the music to spread the political messages of the revolution.

How did the Earkestra come about?

There is a collective of about 40 musicians, so even if it’s Christmas there will always be a band of 13 or 14 people playing. The idea came from Thelonius Monk’s band in New York – they made money on the weekend and then on Mondays they played for fun. In Berlin it’s just €5 entry, before they played for the beer. And there’s no hierarchy in the band. In Bamako the solos were decided during the performance while they were playing.

What is your approach to film-making?

You can say it’s three key words: reality, truth and realism (as described by German filmmaker Eberhardt Fechner). There is the reality, and my perception of reality, which will be different from other peoples’ perceptions, which leads to speaking my truth.

But then there is the third word, which doesn’t exist in French or English – Wirklichkeit, the effect that reality has on us, the way the music ‘works’ on us. It also has to do with consciousness. Then in the next step we express the effect that this reality has on us, which is our truth, and realism is my style to speak my truth.

But then there is the third word, which doesn’t exist in French or English – Wirklichkeit, the effect that reality has on us, the way the music ‘works’ on us. It also has to do with consciousness. Then in the next step we express the effect that this reality has on us, which is our truth, and realism is my style to speak my truth.

Trust is important in achieving chords, like a collective consciousness.

Yes, it has to be that way – and this music is a reflection on our lifestyle, how we live.

That film about techno in the festival was sad, the beat is so simple Bam – Bam – Bam, and everyone is disconnected from other people. Jazz is a collective experience, and the way of experiencing music reflects on the person’s life in general. Jazz happens in the moment and when the stars align there will be a special moment, but you need to be patient and be open for it. I learned a lot from being with these guys and this lifestyle is precious. With jazz you feel connected to the audience and to the musicians, and that’s why they play these Monday concerts.

There was a scene where Schorsch was arguing with one of the African musicians who refused to play his style, until Salif Keita settled it. What was that about?

Georg Pfister, aka “Schorsch” lived in Havana for a long time, is married to a Cuban woman and played a lot with musicians from there. He is the band’s specialist for Clave-Rhythms, playing tenor sax, and he is also known worldwide as a saxophone doctor.

One of the most thrilling songs we discovered was Badiala Malé, the very first Song Salif Keita ever performed on stage, as he told me in an interview.

Each of the band members arranged some songs for the big band and Schorsch picked Badiala Malé. The original version sounded very Cuban-like to Schorsch, so he re-arranged it and put the typical Cuban Clave on it.

They were rehearsing the song in Bamako in Salif’s Studio Moffou, when Cheick Tidiane Seck who was like a producer during almost all of the recordings, complained to Schorsch that this Cuban Clave is inverted, different from the original Mandinka clave coming from Mali. The argument is rather theoretical, especially for this rather simple clave. It just depends on where you start counting. But for Cheick it was a matter of national pride: these rhythms came to Cuba with slavery, and later the Cubans developed their own beats, split up from Mandinka culture, and eventually reversed the Malian Clave. But even if these Malian Bands like The Rail Band were influenced by Cuban music, they always made sure to play their own Malian Rhythms.

Once Salif came in, he realized that the “beat-battle” was about to hinder a cooperation, he told Cheick that they should be indulgent with that version, I think he was also impressed by the tightness of the German band.

Later, the band decided, with their own sort of swarm-intelligence, that they would re-reverse the clave as a sign of courtesy for the Malian musicians.

In the film there was a session of hand-clapping Claves after Salif has left the building, which was the moment when some German

musicians understood the core of that Cheick-Schorsch argument and convinced him to relax on that point. Schorsch’s original clave is still the backbone of the song, but the Clave instrument itself is not on the song anymore.

(Photos supplied by the interviewee and authorised for publication)

.jpg)