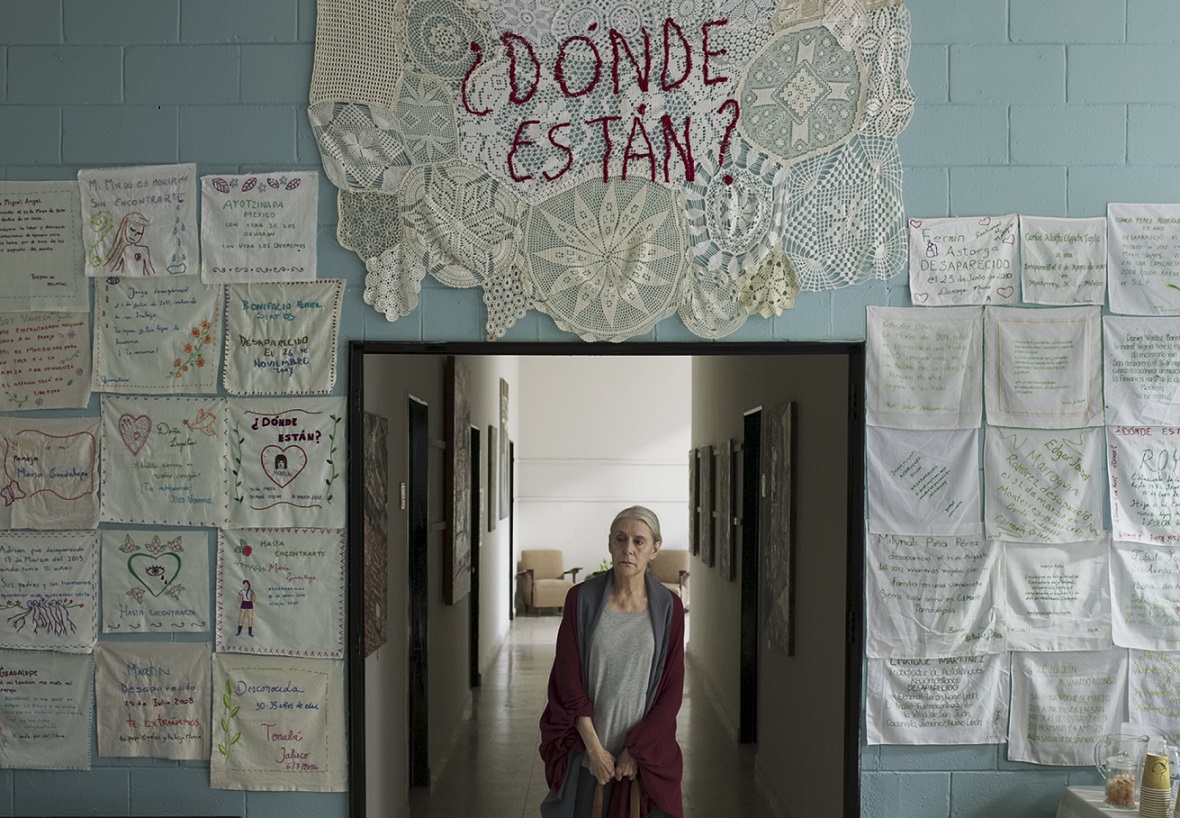

Mexico is suffocating under a wordless horror of gangsterism much of it directed against women, and the government is paralysed by internal corruption and inefficiency. A new film focuses on the silent interior worlds of mothers and family members whose lives have been wrecked but must carry on day to day.

Graham Douglas

Mexico gave us soap operas and films about bandits; we go to Cancun to sun ourselves and to Yucatan or Mexico City to marvel at Mayan and Aztec cultures.

Brazil has magnificent beaches, and its soap operas (telenovelas) are exported around the world, but nowadays it is known globally for Amazon deforestation and the murders of journalists, so Lula’s government is strenuously trying to stop the ecocide. Mexico also has national epidemics of femicide and murders of journalists, but it doesn’t have the same global media profile. Natalia Beristain whose new film “Ruido” (Noise) is now available on Netflix believes that this is partly due to the overload of horror – few people want to see more of this news.

Femicides more than doubled since 2015: they reached 968 in 2022, or 1.43 per 100,000. In Brazil it was 1.40.

One of her objectives in making this film was to overcome this anti-horror inoculation by showing instead the interior life of the mother of a disappeared daughter, in struggle and in solitary moments.

Julia is played by Natalia’s mother, who has been an actor for 50 years, and Natalia says: “If I have a social conscience, it’s because of her”.

I spoke to Natalia for The Prisma after her film was shown at the Mostra de cinema de America Latina in Lisbon recently.

Were you threatened by anyone during the making of the film?

Were you threatened by anyone during the making of the film?

Only by a feminist group! The film is branded Netflix but originally it was funded by the Mexican government. We shot the parts with Julia as herself in Mexico City and the rest in San Luis Potosi State, which was less violent then, and I asked the local feminist groups if they wanted to take part in the final scene at the university where a ‘government building’ is occupied. One group didn’t want anyone to participate because some university staff had been accused of sexual abuse and abuse of power – which we didn’t know about. I went ahead because there was little chance of finding another institution where such allegations are not being made. Occupying the building is now an annual event on March 8th, International Women’s Day.

Did you need police protection?

Yes, because many journalists have been murdered, but you also need to know who the bad guys are and get their agreement – it’s complicated in Mexico. When we returned to the city the art department people stayed behind to pack up the location, and they got caught in crossfire between the military and a criminal gang.

Your other films have focused on women’s stories. Why did you want to make this film?

Your other films have focused on women’s stories. Why did you want to make this film?

I’d been thinking about it for over a decade but didn’t feel strong enough professionally or emotionally to deal with this kind of story, and I hoped this femicide would stop. I continued making films and I also became a mother, which made me want to understand the madness that we live under.

“Ruido” has been praised for showing the interior world of Julia both while searching and at home alone.

This story needed to be told as fiction because as an outsider you get the impression that femicides, disappearances, corruption, the narcos, the government – are all separate. Fiction allowed me to show how they are intertwined, which is why it is so difficult to stop the criminality. I interviewed many women who were searching for relatives who had disappeared through the years, and I realised that one of the most terrible things apart from the loss of their loved ones, is that their lives are broken, they still have to carry on working, paying the rent and living day to day. It’s easy to see them only in terms of their missing relatives without understanding this.

It reminded me of a sci-fi horror film about mysterious disappearances caused by aliens but it is real. Can anyone understand this if they haven’t lived through it?

Having it shown on Netflix is a paradox – how to tell the story without it being seen as exploitation. I used to say this film shouldn’t exist or only be about a parallel reality, but it is real, and it was important for me to get into that.

Having it shown on Netflix is a paradox – how to tell the story without it being seen as exploitation. I used to say this film shouldn’t exist or only be about a parallel reality, but it is real, and it was important for me to get into that.

I also wanted to understand the madness, although there are no simple explanations. But through interviewing the families I realized that this violence touches everyone either directly or through knowing someone. It started in Ciudad Juarez on the US border nearly 20 years ago but now it’s everywhere, and we live with it every single day. Only one of 32 states in Mexico doesn’t have a searcher group and many have more than 10. There is still a tendency to think that it only happens to those who know the wrong people. And if it weren’t for these civilian groups who are doing the work that the State should be doing, we wouldn’t know so much about what is going on. Recently, in Sonora State a civilian group discovered 30 mass graves, and searchers are being kidnapped or murdered.

This year there are presidential elections and the present government which is supposed to be the most left-wing that we’ve ever had, is putting out figures claiming that the number of disappeared people is less than those who are searching for their relatives say – because it doesn’t look good.

The police cynically referred to dismembered bodies as ‘cocinado’ (cooked) and commented about the morgue truck – which drives around collecting dead bodies – saying ‘they’re usually migrants’. The policewoman pretends to help with a list of names that is actually 3 years old. How can these people be made to do the jobs they are paid to do?

The police cynically referred to dismembered bodies as ‘cocinado’ (cooked) and commented about the morgue truck – which drives around collecting dead bodies – saying ‘they’re usually migrants’. The policewoman pretends to help with a list of names that is actually 3 years old. How can these people be made to do the jobs they are paid to do?

There are two aspects to this – certainly there are people inside the local and national government who are part of the problem, who are working for both sides, that’s a reality and everyone knows it. There are also people trying to do their job, but they cannot overcome the system. They don’t have the resources and if they try, someone above them will tell them to stop. It’s so deep that it’s beyond control.

The film is a joint Mexican-Argentinian production. Were you influenced by the history of the disappeared in Argentina?

Yes, the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo were an inspiration, but disappearances are a problem all over Latin America, whether by militias, narcos or La Mara.

But what happened in Chile in 2019 influenced me more and changed the ending of the film. El Estallido Chileno was the young women in the metro after the price increases saying: We can’t take this anymore”, which became a national movement.

And in Mexico in 2020, a group of mothers whose families had suffered disappearances or femicides, occupied the National Human Rights Association building. On September 15, Independence Day the President shouts ‘Viva la Independencia’ from his balcony, which is known as El grito (The shout). They organized their own “Anti Grita” and put pink moustaches, on paintings of the politicians of the revolution.

And in Mexico in 2020, a group of mothers whose families had suffered disappearances or femicides, occupied the National Human Rights Association building. On September 15, Independence Day the President shouts ‘Viva la Independencia’ from his balcony, which is known as El grito (The shout). They organized their own “Anti Grita” and put pink moustaches, on paintings of the politicians of the revolution.

(Photos from the production company MR.WOO, supplied and authorised for publication.)

.jpg)

Very interesting Graham.