Hannah Höch saw the fractured nature of her society and used photomontage and collage to represent and interrogate it. Becoming part of the male-centric Dada movement in Berlin and influencing fellow modernists like John Heartfield, she went on to develop her own aesthetic.

Sean Sheehan

Sean Sheehan

Hoch’s statement in 1929 that “I want to show that small can be large, and large small, it is just the standpoint from which we judge that changes” confirms her break with naïve realism, the belief that everything external to us is just there and we see it as it is.

Her fascination with cutting up and fragmenting images of bodies is an expression of her desire to alienate viewers and in her collages there are also images of colonial artefacts and masks. Such art was anathema to the Nazis and by1935, returning to Germany after six years away, she knew she had to keep her head down and she moved to the outskirts of Berlin and quietly waited in hope of their defeat. When it came in 1945 she could write: “In my soul there is a calmness, such as I haven’t felt for many years.”

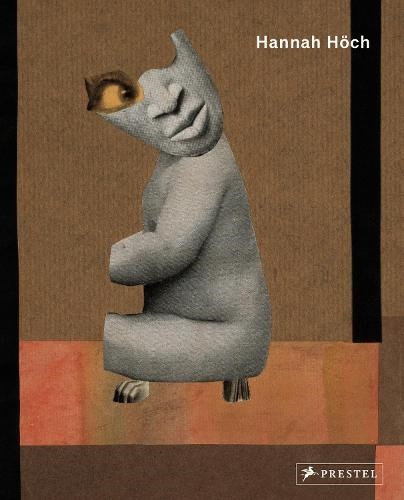

Prestel’s “Hannah Höch”, first published when an exhibition was held at the Whitechapel Gallery, is generously illustrated and has a number of essays covering aspects of her work from `1912 to 1978.

Prestel’s “Hannah Höch”, first published when an exhibition was held at the Whitechapel Gallery, is generously illustrated and has a number of essays covering aspects of her work from `1912 to 1978.

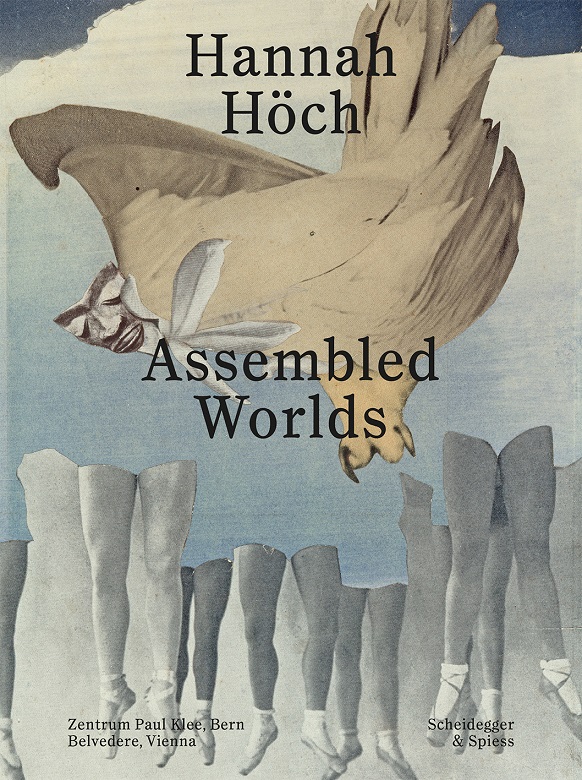

It is an all-round introduction to her achievement and another book, “Assembled worlds”, arising from an exhibition in Bern last year and from June-October 2024 in Vienna, focuses on Höch’s attention to the world of film and the new visual culture of her time.

It includes a 1948 text by Höch and other important short texts by fellow avant-gardists as well as over 150 colour illustrations.

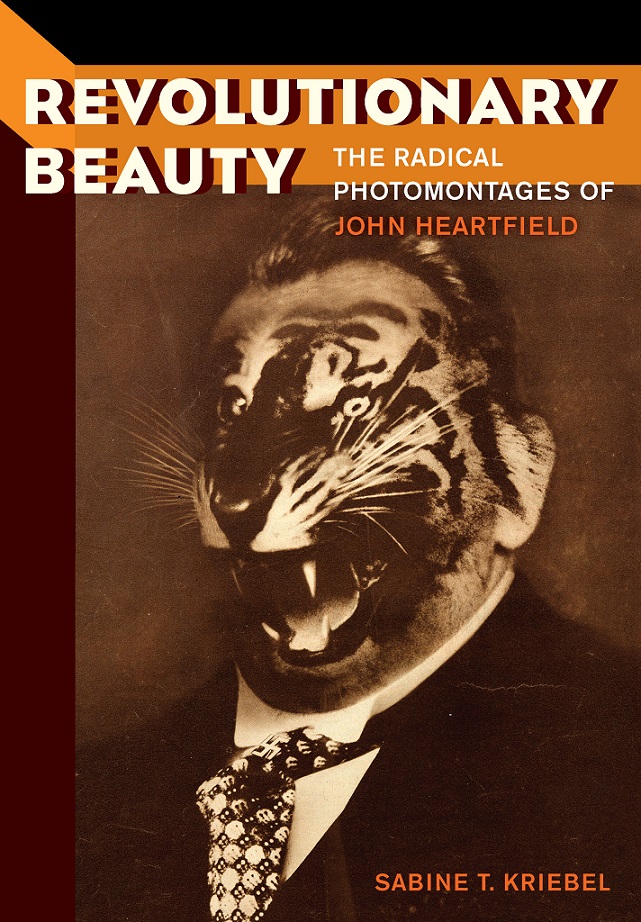

John Heartfield was also part of the Dada movement and the way he put photomontage to sustained political use with the rise of Nazism is the subject of Kriebel’s “Revolutionary beauty”.

Her study, scholarly but accessible, is the most detailed account of an artist who is strangely neglected in histories of 20th-century art despite his influence. Each of her chapters begins with a close look at one of his photomontages before widening the scope of inquiry. Kriebel sees his work – and this is what she successfully documents – as concerned with the “continuing anomie of capitalism” and how his “suffusive wit” becomes “a spur to our conceiving alternatives”.

In the 2022 portrayal of Julian Assange by the vital British artist Peter Kennard, the title of whose own book “Visual dissent” serves to show what is common to Heartfield and Höch, the continuing influence of John Heartfield is keenly felt.

In the 2022 portrayal of Julian Assange by the vital British artist Peter Kennard, the title of whose own book “Visual dissent” serves to show what is common to Heartfield and Höch, the continuing influence of John Heartfield is keenly felt.

“Hannah Höch”, Whitechapel Gallery, is published by Prestel; “Assembled Worlds”, edited by Stella Rollig, Martin Waldmeier and Nina Zimmer, is published by Scheidegger and Spiess; “Revolutionary beauty: the radical photmontages of John Heartfield” by Sabine T. Kriebel, is published by University of California Press.

.jpg)