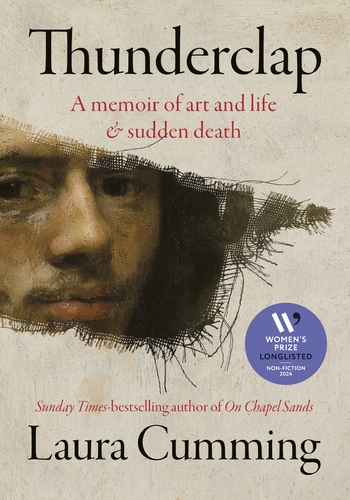

The painting by Fabritius that features in the opening pages of Laura Cumming’s “Thunderclap” – it could be said to be the inspiration for the book – is to be found in Room 16 at London’s National Gallery.

Sean Sheehan

Sean Sheehan

It shows a man sitting at a street corner, two musical instruments by his side, his thumb pensively posed on his chin.

The scene is a pregnant one, bringing to mind Fredric Brown’s two-sentenced (extremely) short story: “The last man on Earth sat alone in a room. There was a knoc k on the door.”

Fabritius is not painting the last man but his picture of a subjectivity alone and waiting leaves the viewer, like Brown’s reader, in a state of unresolved expectation.

Like other art of the Dutch Golden Age (late 16th– to late 17th century), the work of Fabritius can be downgraded by emphasising its mimetic quality.

Art, it has been said, aspires to more than imitating appearance but this seems philistine when looking at the paintings in Room 16. Cummings quotes Joshua Reynolds, the 18th-century Establishment artist – “…their merit often consists in the truth of representation alone” – and such a remark is representative of a blindness to what she calls, referring to Vermeer, “transcendent fictions” in art.

“Thunderclap” is a celebration of what is marvellous about the art of the Dutch Golden Age and praise for her book has been lavish because she communicates her allegiances without sounding like an art critic.

She loves the work of Gerard ter Borch and writes how, coming across his paintings in galleries around the world, there is a warm feeling ‘like coming home’ and she attributes this partly to his liking for portraying his sister Gesina. She appears in “A woman playing a lute to two men” and for Cummings she is “the most attractively radical heroine in Dutch art’ because of the way she is seen to counteract what may be lascivious intent on the part of the two men in the picture. She adds her opinion that without Ter Borch, known to him personally, ‘there would have been no Vermeer”.

Another painter she cannot get enough of is Hendrick Avercamp and his winter landscapes. Snow for him played the role of cherry blossom in Japanese art but it was not fragile beauty he sought to capture on canvas but the communal spirit that possessed people when frozen ice became a playground for adults and children.

Cumming picks out the rosy hue of the building on the right, complementing the pink in the sky on the left, five magpies on parapets and details of class difference. Everyone is preoccupied and, she observes, like people talking on mobile phones, they think they are invisible.

“Thunderclap: A memoir of art and life & sudden death” by Laura Cumming, is published by Chatto & Windus. The National Gallery is free to visit.

(Photos from the National Gallery, authorised for publication.)

.jpg)