Arriving in the United Kingdom 35 years ago from Colombia, Carlos Corredor, delves into his experience of migrating to what he referred to as “the new world” and the inner frustration endured in adjusting to the array of cultural differences. He is the director of a health service for Latin Americans and devotes his time to helping the diaspora .

Zalayka Azam

Zalayka Azam

“I love it here; this is my country.” This is how he expresses the sense of liberation he has found since moving to England, where – soon after arriving – he began to show his commitment to helping immigrants as a “lifetime job,” demonstrating his passion and dedication to guiding those in need of support.

When he first came to the UK, Carlos received help from an English family who provided support during his transition to relocating to St Albans, Hertfordshire. In an area where “everyone was British,” he began familiarising himself with English culture, noticing that British people “admire the differences.”

He felt accepted and inspired to emulate the same welcoming nature towards those who had undergone similar hardships of experiencing violence and income instability.

Passionately, he says that he “wanted others to have a similar experience” as he had when he arrived here: “I already had accommodation, and I did not need to worry about food or work; they helped me.” These circumstances highlight the importance of receiving assistance in alleviating the stress associated with migrating to a different country. His experience has been so positive that he compares his transition to the UK to “entering a new world,” where the alternate realm offers safety, freedom, and comfort, despite needing to adjust to the new way of living.

A journey starts

A journey starts

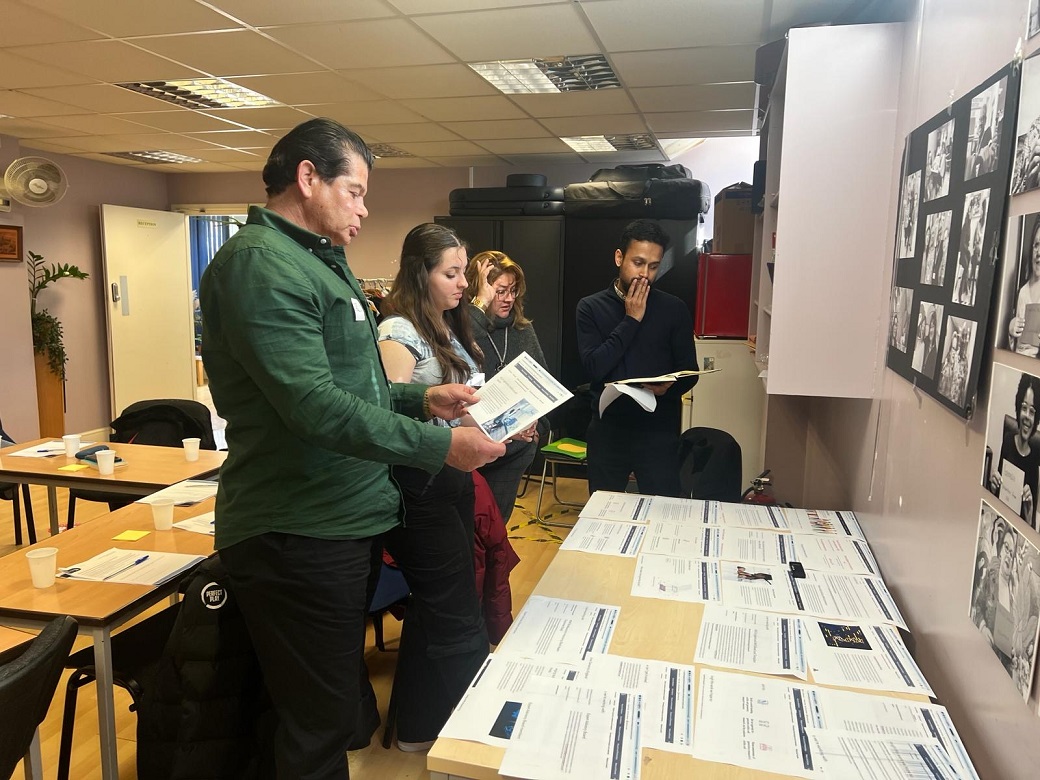

In the late 80’s, he was asked to visit an HIV patient by the Colombian embassy. Returning a week later to the hospital and seeing that the patient had made a significant recovery and was beginning to live a normal life, he was inspired to continue visiting patients in the chaplaincy. From there he began 30 years of helping immigrants with HIV, especially Latin Americans, to access health and other services they need.

This experience was the origin, years later in 2020, of the story of Aymara, which grew as a way to connect with Latin Americans coping with sexual health issues. One of the first people to fund them was Elton John, which motivated Carlos to continue searching for funding, along with help from the community through their volunteers.

His aim to start working with other ethnic minority groups came from noticing that most of the people in London who are immigrants endure similar issues:such as not speaking English, being uncertain of how the system works, and having a poor understanding about immigration status. Carlos disheartendly remarked that “they have very little feeling of belonging, so they aren’t empowered to seek help from services,” highlighting the harsh reality of many immigrants when feeling unwelcome in the country.

To provide a solution for the alarming statistic that 1 in 5 Latin Americans are not registered with a GP, Carlos outlined the principal mission of Aymara, which is “linking communities through easy access to mainstream services so we can improve access for the people.”

By providing disadvantaged minorities with fair opportunities and reducing inequalities, Carlos’ work continues to inspire and demonstrate the power of community.

In his view, issues related to health with other ethnic immigrants occurred during Brexit, leading us to question why newcomers are vastly uninformed about the services and opportunities they could benefit from. “There’s no information out there at all for them to access.” To combat this issue, he firmly states that his mission is to “inform and to tell people they are welcome here.”

Experiencing cultural differences

“People here eat a lot of fried food; it’s irrational to come here and eat burgers when it’s not in our culture”, Carlos says.” The sociocultural aspect of food is intrinsic to cultural identity, significantly impacting how difficult it is for immigrants to adjust to an entirely new culture.

Raised in a tropical country, he speaks about the weather and seasonal changes in the UK and having to adapt to the colder conditions in an act of survival, describing it as a “constant battle.” In addition to this, he talks about the issue of pre-set heating in the winter in temporary accommodation for some immigrants: “Without being able to control the heating, it makes life uncomfortable for them because it’s too hot, even if it’s cold outside.”

“We [immigrants and non-immigrants]don’t think these cultural differences and issues are important, but they are,” he remarks, demonstrating the underlying and undiscussed issues that immigrants face.

In immersing the collectivist culture of Latin America in the UK, he states that one of the aims as director of Aymara is to “make people socialise,” creating a collaborative and encouraging community. With over 8 million households in the UK eating meals alone, the Colombian contrasted the cultural importance of togetherness, how in Colombia “we always eat together, whereas it’s more common in the UK to eat alone.”

His yearly returns to Colombia to visit his friends and relatives are “rewarding experiences” and despite not having any family members in the UK or Europe, he emphasises the importance of friends to “look after you”.

He also emphasizes how solidarity and friendship between first-generation migrants facilitate teaching people how to deal with issues such as immigration documents through the learning and sharing of experiences.

Sexual health in migrants

Sexual health in migrants

Adopting the UK’s liberal stance towards sexual health, Carlos expresses how, in Latin American culture, sexuality is still “very taboo,” as people still avoid talking about certain issues. His work in providing free HIV and STI testing among migrants encourages the help of volunteers to combat the biggest spreader of sexual diseases: ignorance.

The provision of accurate information is crucial, as he points out that “with the improved medical situation and new HIV treatment, it’s a chronic condition and no longer a death sentence, so people can live normal lives.” He also states that “it is important to mention that for people on treatment, it’s undetectable, and you cannot pass anything on to others.” His workshops to reach individuals to challenge myths and misinformation regarding sexual diseases help combat the stigma surrounding sexual health.

One of his most surprising moments when offering STI testing to people in Elephant and Castle, London was when members of the community came to help get people tested. He adds: “It’s beautiful when the community responds to your ideas.”

Regarding the revised immigration rules in the UK, I asked Carlos about his views toward the changes made to the law, he replied, “I’ve seen many of these laws coming and going, they have always been the worry to stop the people (immigrants) from coming here… but in the end if we want to do something we will do it.”

Regarding the revised immigration rules in the UK, I asked Carlos about his views toward the changes made to the law, he replied, “I’ve seen many of these laws coming and going, they have always been the worry to stop the people (immigrants) from coming here… but in the end if we want to do something we will do it.”

(Photos supplied by the interviewee and authorised for publication).

.jpg)