Exhibitions like the one currently on show at The Photographers Gallery in London are becoming precious at a time when art photography is increasingly devoted to personal projects of meagre public interest or so concept-driven as to risk disappearing up its own fundament.

Sean Sheehan

Chris Killip, in telling contrast, photographed those whom, he once said, “Had history done to them”.

He took pictures of men, women and children who did not benefit from an economic system that detrimentally determined their live chances.

This could be a recipe for defeatism but Killip deployed his camera with a tenderness and precision that bore witness to what John Berger expressed when he wrote of photography’s ability to mount an “opposition to history”.

Killip (1946-2020) was seventeen years of age when he came across a Cartier Bresson photograph in a magazine, a street scene with a boy carrying two large bottles. He remembered it as an important moment in his life: “It stopped me in my tracks and held me spellbound.”

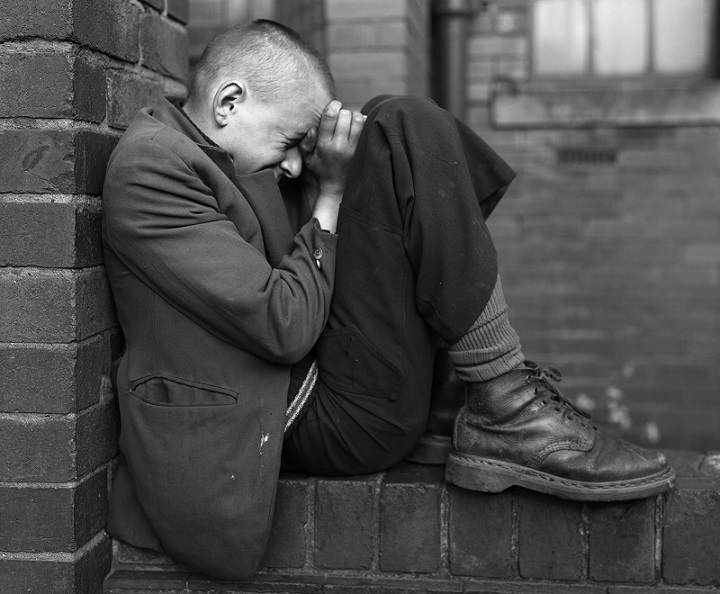

Looking around at the lives of the working-class in the Britain in the 1970s and ‘80s, bleak desperation was always on the horizon and Killip’s 1976 picture of a crouched youth in Jarrow on Tyneside seems emblematic of this sense of being on the brink of despair.

The image is characteristic of Killip’s attention to the human body as an expression of a social condition but his response to lives hemmed in by a dehumanizing political order is more nuanced and less archetypal than what this photograph represents.

Take, for instance, his “Crabs, people, dogs” taken when he spent time around the North Yorkshire village of Skinningrove in the early 1980s.

The composition of its coastal scene –a man and woman looking out to sea, an unseen baby in a pram, a driver at the wheel of a parked car on a slipway, a cart of crabs and two dogs glancing alertly in different directions– defies narrative interpretation by not telling but showing an undefined apprehension, an open-ended waiting. This is not hopeless desperation and there is awkwardness in the scene that carries an air of mystery. Even when people are physically distanced from one another, they share something that is vital to their being and it is bound up with the particularity of their community and the larger political landscape that threatens their autonomy.

Another of his Skinningrove photos is of a family of four out for a Sunday walk in the vicinity of their village; inured to circumstance, they are brought together in a silence that inhabits the space around them.

There are similarities between this photo and the ‘Crabs, People, Dogs’ one: the two men’s postures suggest a longing for something and the women’s presence echoes the desideratum.

They all have their backs to the camera, not in defeat but with an expectation for something ahead. The two dogs stand in anticipation; the driver in the stopped car on the slipway also waits.

“Chris Killip, Retrospective” is at The Photographers Gallery, London until 19 February.

(Photos supplied by the gallery and authorised for publication)

.jpg)