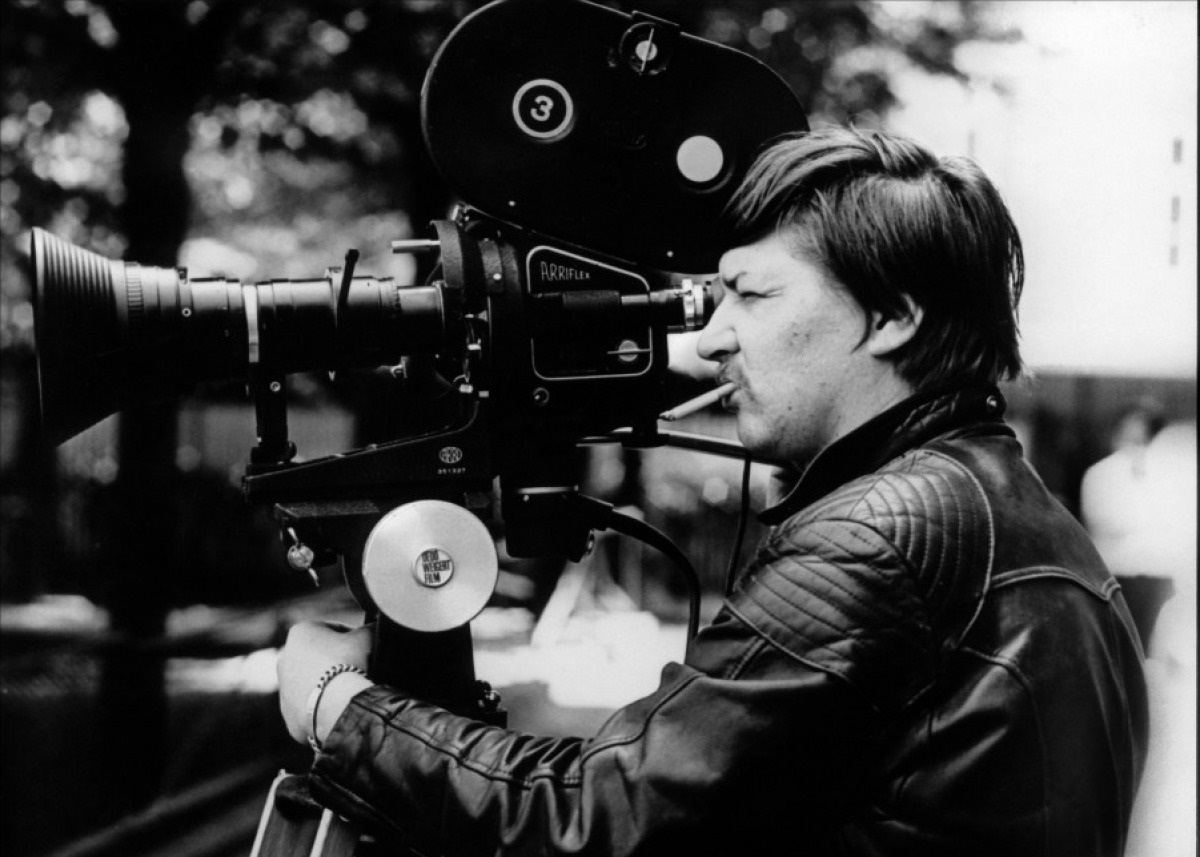

Words like provocative, unruly, radical easily come to mind but seem inadequate when discussing Rainer Werner Fassbinder, the hyper-prolific filmmaker whose untimely death in 1982 signalled the end of a politically tumultuous period in German history.

To be more exact, the history of the western half of post-World War II Germany. Liberal pieties go out the window when describing what took place there during the 1970s.

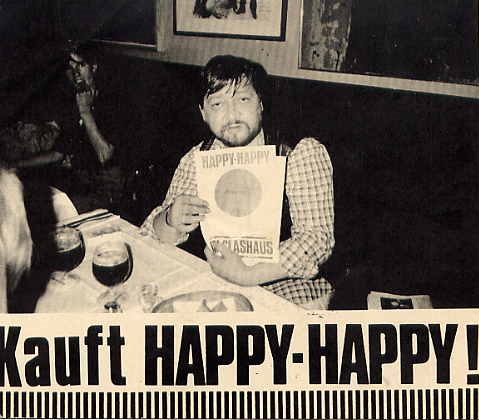

As Ian Penman was becoming a hip music journalist in the late 1970s London he found in Fassbinder’s films an exotic – non-British, that is – expression of the post-punk rage and unfocused angst that he saw around him in London.

He was too young for the Angry Brigade to have registered in his consciousness and did not know enough about West Germany’s Red Army Faction to feel the pulse of Fassbinder’s politics.

But this pulse has become the heartbeat of contemporary Europe and Fassbinder could feel it all around him – systematic surveillance, repressive legislation, state violence – and Penman, looking back at the filmmaker that still fascinates him, recognises his prescience in “The third generation”.

When that film was made, 1979, the first and second waves of RAF action had given way to what Fassbinder saw as a ‘pseudo-adventure of taking on the system’, going on to say it was a godsend to the authorities: ‘If these terrorists did not exist, this state would have to invent them. Perhaps it even has?’

When that film was made, 1979, the first and second waves of RAF action had given way to what Fassbinder saw as a ‘pseudo-adventure of taking on the system’, going on to say it was a godsend to the authorities: ‘If these terrorists did not exist, this state would have to invent them. Perhaps it even has?’

There is an essential scene in his “Germany in Autumn” (1978) where a man is seen digging for German history, metaphorically and literally, with a spade in a German forest. Fassbinder attacks the German middle class for an acquiescence which is historically specific.

It is not that of their parents’ generation that sustained Nazism in the 1930s but the acquiescence of the 1960s and ‘70s that willingly forgot what their parents did. Nowadays, of course, Germany’s memory culture is held up as a virtue that puts to shame countries like Poland and Ukraine but valorizing memory culture as a national act of atonement may have a narcissistic aspect and Fassbinder as alert to this.

Fassbinder would have loved the 2014 movie “Phoenix”, for its nuanced portrayal of middle-class German amnesia in the years immediately following the end of World War II and its sweet use of the “Speak low” song rendered by the woman who survived the Holocaust.

Fassbinder also used song to devastating effect in his 1982 film “Veronika Voss” where “Memories are made of this”, the lyrics of which are sick in the context of post-Holocaust Germany, sums up the self-induced amnesia that became the country’s drug of choice in the 1950s.

Penman’s book about the filmmaker is written with brio, mixing the anecdotal with the autobiographical, and shares some of the kinetic energy that characterizes the films he reflects on.

Best of all, it helps rescue Fassbinder from the relative obscurity he does not deserve.

“Fassbinder: Thousands of mirrors”, by Ian Penman, is published by Fitzcarraldo Editions.

.jpg)